Developing A Framework To Describe The Interaction Of Social And Intellectual Capital In

Organizations

Ramin Vandaie, George

Washington University

ABSTRACT:

Based on an extensive review of the literature on theories

of social and intellectual capital, network analysis, and social information

processing, a conceptual model is developed to describe the interaction of

social and intellectual capital in organizations. According to the major line

of research on social capital in organizations, social capital comprises

structural, relational, and, cognitive dimensions. The conceptual model of this

paper identifies the cognitive dimension of social capital to be the major

point of interaction between social and intellectual capital. The theory of

social information processing is used to describe the nature of this

interaction.

Keywords: Organizational Knowledge Creation, Intellectual Capital, Social Capital, Social Information Processing

1. Social Capital In

Organizations

It has been proposed in a fairly new line of organization research that a better understanding of the organization could be presented in the form of a social community that specializes in the fast and efficient creation and transfer of knowledge (Coleman, 1988; Conner and Prahalad, 1996; Grant, 1996; Nahapiet and Ghoshal, 1998). This perspective is in contrast to the traditional transaction-cost theory which has its grounds in opportunism in the market. The knowledge-based view attributes a new capability to the organization which is the capability of creating and sharing knowledge that gives the organization its distinctive advantage over other institutional forms such as markets (Grant, 1996). An advantage which stems from the organization’s facility for creation and transfer of tacit knowledge, its structured principles of coordination and communication, and its nature as a social community (Nahapiet and Ghoshal, 1998). This particular capability of organizations has been best described by introducing the concept of “social capital” (Coleman, 1988; Nahapiet and Ghoshal, 1998). The driving idea of social capital is that networks of relationships are valuable resources supporting any social affair by crediting all individuals with a collectively-owned capital. A broad and illustrative definition of social capital includes the networks of relationships as well as the resources and assets mobilized through these networks. Therefore, social capital could be defined as the actual and potential resources embedded within and available through the networks of relationships in an organization (Nahapiet and Ghoshal, 1998). Social capital is not a single entity. Rather, it encompasses a variety of entities that all consist of some aspects of social structures and facilitate certain actions of actors within that structure. Unlike other forms of capital, social capital inheres in the structure of relations among actors and does not belong to any single individual within the network (Coleman, 1988).

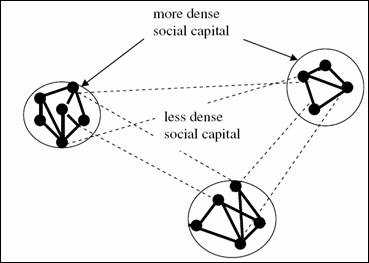

The capability of organizations in fostering dense networks of social interaction among individuals distinguishes them from other institutional structures such as markets. In the inter-organizational networks of relations in markets the possibility of forming such strong ties is far less. This causes the social capital to be denser inside the organization as opposed to the outside. This concept is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1: High Density Of Social

Capital Within Organizations As Opposed To Inter-Organizational Environment

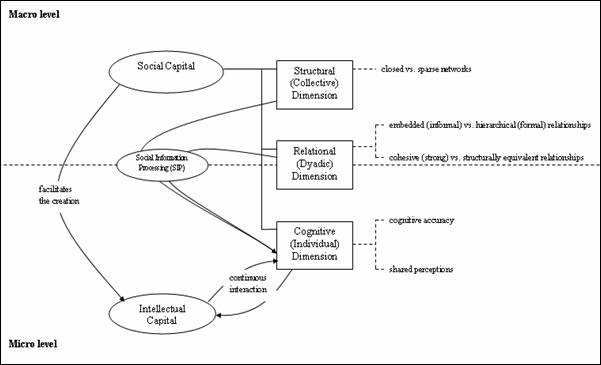

Researchers attempting to identify and explain the different attributes and dimensions of social capital have, to a great extent, agreed on three dimensions to describe the social capital in organizations: structural, relational, and cognitive (Nahapiet and Ghoshal, 1998). Distinctive attention to these three dimensions helps a lot in analyzing the origin, evolution and effects of social capital in organizations and serves as a foundation to the conceptual model proposed in this paper. This paper’s proposed model of interaction among the three dimensions of social capital as well as the interaction between the social and intellectual capital in organizations is presented in the 2. The model consists of two major sections: the macro level and the micro level. The macro level mostly refers to the concept of social capital. However, some aspects of social capital fall under the micro level which also includes the concept of intellectual capital. From a holistic perspective, the macro and micro levels relate to each other through the facilitating role of social capital in the creation of intellectual capital (Coleman, 1988; Nahapiet and Ghoshal, 1998). However, the interrelation between these two levels is best described using the theory of Social Information Processing (SIP) (Salancik and Pfeffer, 1978). The SIP lies on the edge between two levels and conveys the influence of the structural and relational dimensions of the social capital onto the cognitive dimension. The main thesis of this paper is that the cognitive dimension of social capital, which is shaped by the structural and relational dimensions of social capital through the process of SIP, is the major point of interaction between social and intellectual capital in organizations. The following sections present extensive reviews of various lines of literature that were used to develop different parts of this model followed by discussions of the proposed links among these different parts to support the thesis of this paper.

Figure 2: Model Of Interaction

Among Social And Intellectual Capital

2. The

Structural Dimension Of Social Capital

The structural dimension concerns the properties of the network as a whole and refers to the overall pattern of connections among individuals which in turn indicates who people reach for social resources and how they reach them. Important aspects of this dimension include the presence or absence of ties between actors, and network configurations explored through measures such as network density, connectivity and centrality (Marsden, 1990; Borgatti and Cross, 2003; Cross et al., 2001). From the perspective of the structural dimension, there is a strong belief that social capital benefits from closure (Coleman, 1988), that is having a dense organizational network with all actors connected to each other. However, it has also been argued that there are certain benefits accrued to a social network from the increased efficiency available through sparse networks (Granovetter, 1973; Burt, 1992). Sparse networks distribute the time and energy of focal actors on a greater number of ties allowing them to access more novel information from a wide range of resources and increase their opportunities to broker the relationship between their contacts. Sparse networks, however, seem to be more advantageous for relationships with external sources than for relationships within the organization since the brokering opportunities provided through sparse networks are mainly used in the context of market transactions and inter-organizational relationships (Granovetter, 1973; Hansen,1999, Ahuja, 2000; Rowley et al., 2000). Since the focus here is on the properties of social capital within the organization, I adopt Coleman’s (1988) notion of network “closure” to describe the structural dimension of my model. As Coleman (1988) argued, social capital within the organization is leveraged when the actors tends to “close” the network by creating and maintaining a dense network of interpersonal relationships. The closure of the social structure gives rise to norms of action based on mutual and collective trust and encourages every individual to play an active role in the network. These shared norms of trust and reciprocity tend to form individuals’ cognition of the network in which they are embedded. This influence is conveyed onto individuals’ cognition through the process of social information processing which will be discussed later.

3. The Relational Dimension Of Social Capital

The relational dimension of social capital takes the center of attention one step farther from macro to micro level. The relational dimension lies on the edge between macro and micro levels and is considered as a transition from the holistic view provided by the structural dimension towards a detailed view of the role of individuals. The relational dimension of social capital is used to describe the properties of interpersonal relationships people develop as the result of ongoing interactions within the organization. In general, this dimension concerns the social assets formed and shared through relationships. Interpersonal relationships have been classified based on their formal organizational status into hierarchical (formal) and embedded (informal) relationships (Podolny and Baron, 1997; Uzzi and Lancaster, 2003). Within organizations, ties and networks exist among formal positions as well as among individuals. Organizations often picture their network of formal positions by workflows or organizational charts. The ties among formal positions are independent of the individuals occupying the positions. The networks of task-related advice in organizations are generally inherited by virtue of the formal organizational positions (Podolny and Baron, 1997). After all, the task-related information and advice that an individual needs and can provide to others is mainly determined by the formal organizational position that the individual occupies. As a consequence, formal organizational hierarchy has a significant role in circumscribing and structuring the network ties. On the other hand, the embedded (informal) relationships are generally based on interpersonal attraction and norms of trust and mutual benefit (Uzzi and Gillespie, 2002; Uzzi and Lancaster, 2003). They are formed and maintained mostly on a discretionary basis and are not strongly affected by the formal hierarchy in the organization. The distinction between hierarchical and embedded relationships should not be overstated, though, as the relationships in organizations are normally a hardly separable blend of the two types. The formal hierarchy is the primary determinant of who should know what. However, over the course of regular interpersonal interactions, the formalities tend to be moderated by norms of social behavior (Nelson, 1989; Nahapiet and Ghoshal, 1998). The distinction, however, is useful when investigating the origin and evolution of relationships in organizations.

In addition to the distinction based on the origin of organizational relationships, classifications based on the nature of the relationships are also dominant in the network literature. The idea of strong and weak ties has long been an issue of debate among network researchers. Various positive and negative effects of maintaining a network populated with strong or weak ties have been identified in different contexts (Granovetter, 1973; Krackhardt, 1992; Bian, 1997; Hansen, 1999; Ahuja, 2000; Rowley et al., 2000; Shane and Cable, 2002; Jack, 2005). Most of this debate, however, concerns the inter-organizational relationships which is not the center of focus in this paper. Within the context of the organization, Shah's (1998) classification of social relationships into relationships with structurally equivalent referents (weak ties) and relationships with cohesive referents (strong ties) is also interesting. Cohesive referents are those that the individual maintains a close and strong interpersonal tie with. While structurally equivalent referents are those who would be source of advice and information only because they share a similar position in the network. Trying to investigate the types of information obtained from each of theses two types of relationships, Shah (1998) discovered that under different circumstances both cohesive and structurally equivalent actors appear to be sources of informational influence. However, the type of information and the manner in which information is sought from these actors show different characteristics. The frequency, intensity, and proximity of interaction in cohesive relationships results in cooperative mechanisms on which the individuals rely to reduce the task-related uncertainty. Moreover, the strength of cohesive ties and norms of reciprocity and mutual trust intensify the influence of the information exchanged. In other words, information from cohesive relationships is viewed as more credible and influential than information from other sources. On the other hand, structurally equivalent actors share a similar pattern of relationships. They could develop a cohesive tie if a direct relationship exists between them, but the inherent competition among individuals in similar structural positions and the fear of appearing incompetent usually inhibits the first-hand access to information from structural equivalents. Shah (1998) suggests that since the direct relationships are absent between such actors, indirect ways of obtaining information such as monitoring become a more preferable information-gathering conduit. Thus individuals may rely on observations and second-hand information-gathering techniques to obtain information from their structural equivalents.

Among the three different classifications of interpersonal relationships reviewed here (i.e. hierarchical vs. embedded, strong vs. weak, and structurally equivalent vs. cohesive), the strong/weak classification seems less relevant since it more concerns the context of inter-organizational relations. A mixed interpretation of the other two classifications, however, serves the purpose of model in this paper. Structurally equivalent contacts, by definition, occupy similar organizational positions and are most likely to be determined within the hierarchical and formal structures defined by organizational charts. Embedded ties, on the other hand, are based on norms of mutual trust and reciprocity and therefore, grow to become cohesive over time. This differentiation is recognized in this paper’s model by adopting the perspective that individuals maintain a balanced portfolio of these relationships. It is naive to assume that the actors who are competitors by definition of their organizational roles will share the same amount of information and knowledge as they share with their cohesive contacts. However, the organizational advantage lies in the capability of motivating the individuals to share more information and knowledge and contribute to the social capital despite the existing competitions. The nature of interrelationships that individuals maintain with others in the organization affects their perception of the network. Relational dimension of social capital acts in parallel with the structural dimension in shaping the cognitive dimension of social capital. The joint influence of the structural and relational dimensions of the social capital on the cognitive dimension will be discussed later on, using the theory of SIP.

4. The Cognitive Dimension Of Social Capital

The third dimension of social capital is the cognitive dimension. The cognitive dimension of social capital explains the shared language and codes that convey the perception of individuals about network of social relations in the organization (Ibarra and Andrews, 1993; Nahapiet and Ghoshal, 1998). The discussion of cognitive dimension completes the transition from the macro to the micro level of the model. The cognitive dimension of social capital describes the perceptions that are made by individuals on others as well as the perceptions that they take from others. Boland and Tenkasi (1995) explained the importance of perception making and perception taking in a social context and key role it plays in knowledge creation. They argued that during the process of perspective making the knowledge required for carrying out a complex knowledge-intensive task known by individuals is perceived collectively by the network. This shared perception of knowledge is then strengthened as they interact in the framework of their social relationships. On the other hand, much of social behavior is based on the assumptions an individual makes about the knowledge, beliefs, and motives of others. This is the beginning of the process of perspective taking where, by increasing the knowledge of what others know, individuals gain the necessary knowledge base for performing a coordinated knowledge-intensive task. Similar to any other organizational process, the processes of perspective making and perspective taking and formation of the cognitive dimension of social capital are the outcomes of interactions among individuals and not their isolate behavior.

The cognitive dimension plays a pivotal role in this paper’s model. As was mentioned in the previous sections, the cognitive dimension is shaped by the joint influence of the structural and relational dimensions. A process which is best explained using the theory of Social Information Processing (SIP). Next section reviews this theory and its application in describing the interaction of social and intellectual capital in organizations.

5. Social Information Processing

In an attempt to illuminate the cognitive dimension of social capital scholars in one line of research introduced the concept of cognitive accuracy. This concept refers to the accuracy of the perceptions that individuals have about the networks of social relations in their organization (Salancik and Pfeffer, 1978; Ibarra and Andrews, 1993). Organizational attitudes and perceptions do not form in vacuums. They are powerfully influenced by social context. Individuals are involved in multi-layer and overlapping webs of relationships that affect their perceptions of the network they are embedded in. In a critique of previously dominating paradigms, Salancik and Pfeffer (1978) argued that it is important to take into account the social context when assessing employee perceptions of organizational environment. The social context in which individuals are embedded affects their attitudes and perceptions. Salancik and Pfeffer (1978) proposed the theory of Social Information Processing (SIP) to explain the formation of attitudes, perceptions, and beliefs about the organizational environment. The theory of SIP suggests that social influences on the formation of attitudes among people in work environments could be a better predictor of organizational attitudes than are individual needs or other individual factors. Arguing that forming attitudes about the organizational environment is an information-processing activity, they suggested that the development of attitudes is a function of the information which is accessible to individuals through their social relationships. According to Salancik and Pfeffer (1978) people depend on their sources of social information to get more accurate information and interpretations of ongoing events within their organization. This social information, in turn, transforms into their organizational attitudes through social information processing. Basing their work on the idea of SIP, Ibarra and Andrews (1993) proposed that the study of social structure in the organizations provides the key to understanding the nature of mechanisms by which SIP affects the formation of organizational attitudes. Individuals are embedded in social structures that influence their interpretations of organizational realities (Cameron and Whetten, 1981; Fombrun, 1983). Different types of perceptions may be affected by different types of network mechanisms and network mechanisms do not operate independent of the relationship embedded in them (Krackhardt, 1990). Included in the model proposed in this paper is the joint influence of the structural and relational dimension of social capital on the cognitive dimension. The social information processing theory provides a means to describe the nature of this influence. Individual cognitions are continuously shaped by the social information that is received and processed through the relationships and individual maintains in the organizational networks. The politics of the organizational network, in turn, increase or decrease the value and attractiveness of the relationships and forces the individuals to reconsider their portfolio of relationships. After all, the amount of time and energy that could be dedicated by the individuals to maintain these relationships is limited. As a consequence, organizational members always try to optimize the benefits that are attainable through their portfolio of relationships under varying network conditions.

The main thesis of this paper is that the cognitive dimension of social capital, shaped by the structural and relational dimensions, acts as the major point of interaction between social and intellectual capital in organizations. It is generally believed that social capital facilitates the creation of intellectual capital (Coleman, 1988; Nahapiet and Ghoshal, 1998). To provide a clear understanding of the concept of intellectual capital in particular and its role in the model in general, next section reviews this concept in details.

6. Intellectual

capital

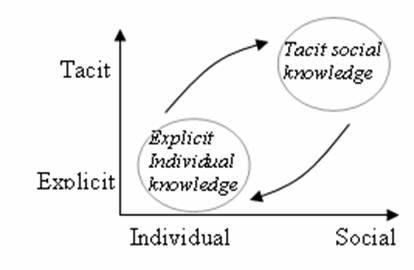

Traditionally, organizational resources have been known to be in the form of tangible capital such as physical and human capital. However, the recognition of knowledge as an important and valuable resource for organizations has gained impetus among organization scholars in the past decade (Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995; Conner and Prahalad, 1996; Grant, 1996; Tsoukas, 1996; Gupta and Govindarajan, 2000; Grover and Davenport, 2001). Some scholars have gone so far to propose that the economic and producing power of the firm lies more on its knowledge integration and intellectual capabilities than its hard assets (Grant, 1996; Conner and Prahalad 1996). This emphasis gains even more and more strength as we move toward knowledge-intensive industries where the success of a company is basically determined by its knowledge and intellectual capabilities. Intellectual capital refers to the knowledge and knowing capability of the organization as it is aggregated from the knowledge of individuals (Nahapiet and Ghoshal, 1998; Johannessen et al., 2005). Intellectual capital represents an organizational capability for action based on knowledge. The concept of intellectual capital acknowledges the significance of socially and contextually embedded forms of knowledge as a source of value differing from the simple aggregation of the knowledge of a set of individuals. When discussing the process of knowledge creation from the lens of intellectual capital, one argument is that only individuals generate knowledge. This argument dismisses the role of the organizations and other social entities in this process. However, it has been widely recognized that the assumption of an atomistic and isolated individual in the discussion of knowledge creation is incomplete. Parallel with Nonaka and Takeuchi’s (1995) idea of knowledge ontology, Spender (1996) proposed a framework for classifying the knowledge in its different formats within organizations which clearly explains the concept of intellectual capital. Spender used a two by two matrix to classify the different types of organizational knowledge in terms of the level of tacitness and the level of collectiveness. This classification is represented in 3. The tacit/explicit dimension is mostly based on Polanyi's (1966) and later, Nonaka and Takeuchi’s (1995) definition of the tacit dimension of knowledge. Explicit knowledge refers to knowledge that is transmittable in formal, systematic languages, while tacit knowledge is personal, context-specific, and therefore hard to formalize and communicate.

Figure 3: Two Dimensional View Of

Intellectual Capital (Nonaka & Takeuchi,

1995; Spender, 1996)

According to Spender (1996), knowledge of individuals must always be considered in the context of the processes of the social entity that relies on that individual. The concept of intellectual capital is the key to reconciling the individual-level view and collective-level view of knowledge in organization. Intellectual capital enables us to describe the emergence of organizational knowledge from individual knowledge. The model in 3 goes beyond the argument that organizational knowledge and Intellectual capital is of two static types of explicit and tacit. It proposes that the intellectual capital in the organization is maintained and leveraged through the interaction of all elements along the two coordinates. This idea has an important implication for the conceptual model and the thesis proposed in this paper which is discussed in the next section.

7. Conclusion,

Interaction Of Social And Intellectual Capital

As mentioned in previous sections, the major point of interaction between the macro and micro level in the model proposed in this paper is the interaction of the intellectual capital and the cognitive dimension of social capital. Intellectual capital within the organization is a product of knowledge integration which is achieved by having perfect knowledge flows among knowledge sources and knowledge seekers (Spender, 1996; Johannessen et al., 2005). To the extent that the obstacles are removed and the flow of knowledge is leveraged, the intellectual capital is fostered within the organization. The idea of the circular process of the evolution of intellectual capital ( 3) could be used here to provide a better picture of the interaction between social and intellectual capital. Intellectual capital is leveraged in organizations as the individuals’ knowledge is aggregated and integrated through social mechanisms. Organizations constantly reorganize their networks of social relations in the hope that they will achieve more efficient mechanisms for transforming the knowledge pool of their individual members into actionable and sustainable intellectual capital. In the course of these reorganization attempts, the individual cognitions of the organization’s social structure are also redefined. This effect can be explained in light of the model proposed in this paper. As mentioned earlier, reorganizations of social structure imply certain changes in the organizational politics for individuals that are conveyed to them through social information processing. As a result of this change in individual cognitions, perceptions of valuable knowledge are also adjusted to accommodate the required changes in the individuals’ positions in the organizational network. These adjustments in knowledge preferences of individuals in turn imply adjustments to the organizational knowledge pool and intellectual capital. In other words, a desired improvement in intellectual capital in the organization is translated to changes in social structure and in particular, the cognitive dimension of social capital. This circle is closed by the reciprocal effect of the changes in individual cognition on the intellectual capital in the organization.

Organizations constantly go through this cycle of interaction between intellectual and social capital and induce waves of change in one by manipulating the other. The success of an organization lies on its ability to minimize the adverse destabilizing effects of this interaction and maximize its promoting effects on the level of social and intellectual capital in the organization.

8. References

Ahuja, G., 2000, Collaboration networks, structural holes, and innovation: A longitudinal study, Administrative Science Quarterly, 45.3, pp.425-455.

Bian, Y. J., 1997, Bringing strong ties back in: Indirect ties, network bridges, and job searches in China, American Sociological Review, 62.3, pp.366-385.

Boland, R. J. and Tenkasi, R. V., 1995, Perspective Making and Perspective-Taking in Communities of Knowing, Organization Science, 6.4, pp.350-372.

Borgatti, S. P. and Cross, R., 2003, A relational view of information seeking and learning in social networks, Management Science, 49.4, pp.432-445.

Burt, R. S., 1992, Structural Holes : The Social Structure of Competition, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 1st Edn.

Cameron, K. S. and Whetten, D. A., 1981, Perceptions of Organizational-Effectiveness over Organizational Life-Cycles, Administrative Science Quarterly, 26.4, pp.525-544.

Coleman, J. S., 1988, Social Capital in the Creation of Human-Capital, American Journal of Sociology, 94, pp. S95-S120.

Conner, K. R. and Prahalad, C. K., 1996, A resource-based theory of the firm: Knowledge versus opportunism, Organization Science, 7.5, pp.477-501.

Cross, R., Borgatti, S. P. and Parker, A., 2001, Beyond answers: dimensions of the advice network, Social Networks, 23.3, pp.215-235.

Fombrun, C. J., 1983, Attributions of Power across a Social Network, Human Relations, 36.6, pp.493-508.

Granovetter, M., 1973, The Strength of Weak Ties, American Journal of Sociology, 78.6, pp.1360-1380.

Grant, R. M., 1996, Prospering in dynamically-competitive environments: Organizational capability as knowledge integration, Organization Science, 7.4, pp.375-387.

Grover, V. and Davenport, T. H., 2001, General perspectives on knowledge management: Fostering a research agenda, Journal of Management Information Systems, 18.1, pp.5-21.

Gupta, A. K. and Govindarajan, V., 2000, Knowledge flows within multinational corporations, Strategic Management Journal, 21.4, pp.473-496.

Hansen, M. T., 1999, The search-transfer problem: The role of weak ties in sharing knowledge across organization subunits, Administrative Science Quarterly, 44.1, pp.82-111.

Ibarra, H. and Andrews, S. B., 1993, Power, Social-Influence, and Sense Making - Effects of Network Centrality and Proximity on Employee Perceptions, Administrative Science Quarterly, 38.2, pp.277-303.

Jack, S. L., 2005, The role, use and activation of strong and weak network ties: A qualitative analysis, Journal of Management Studies, 42.6, pp.1233-1259.

Johannessen, J. A.,Olsen, B. and Olaisen, J., 2005, Intellectual capital as a holistic management philosophy: a theoretical perspective, International Journal of Information Management, 25.2, pp.151-171.

Krackhardt, D., 1990, Assessing the Political Landscape - Structure, Cognition, and Power in Organizations, Administrative Science Quarterly, 35.2, pp.342-369.

Krackhardt, D., 1992, The Strength of Strong Ties: The Importance of Philos in Organizations, in Nitin Nohria and Robert Eccles, 1992, Networks and Organizations: Structure, Form, and Action, Harvard Business School Press, Cambridge, MA.

Marsden, P. V., 1990, Network Data and Measurement, Annual Review of Sociology, 16, pp.435-463.

Nahapiet, J. and Ghoshal, S., 1998, Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage, Academy of Management Review, 23.2, pp.242-266.

Nelson, R. E., 1989, The Strength of Strong Ties - Social Networks and Intergroup Conflict in Organizations, Academy of Management Journal, 32.2, pp.377-401.

Nonaka, I. and Takeuchi, H., 1995, Knowledge-Creating Company, Oxford University Press.

Podolny, J. M. and Baron, J. N., 1997, Resources and relationships: Social networks and mobility in the workplace, American Sociological Review, 62.5, pp.673-693.

Polanyi, M., 1966, The Tacit Dimension, Doubleday & Co., Garden City, NY.

Rowley, T., Behrens, D. and Krackhardt, D., 2000, Redundant governance structures: An analysis of structural and relational embeddedness in the steel and semiconductor industries, Strategic Management Journal, 21.3, pp.369-386.

Salancik, G. R. and Pfeffer, J., 1978, Social Information-Processing Approach to Job Attitudes and Task Design, Administrative Science Quarterly, 23.2, pp.224-253.

Shah, P. P., 1998, Who are employees' social referents? Using a network perspective to determine referent others, Academy of Management Journal, 41.3, pp.249-268.

Shane, S. and Cable, D., 2002, Network ties, reputation, and the financing of new ventures, Management Science, 48.3, pp.364-381.

Spender, J. C., 1996, Making knowledge the basis of a dynamic theory of the firm, Strategic Management Journal, 17, pp.45-62.

Tsoukas, H., 1996, The firm as a distributed knowledge system: A constructionist approach, Strategic Management Journal, 17, pp.11-25.

Uzzi, B. and Gillespie, J. J., 2002, Knowledge spillover in corporate financing networks: Embeddedness and the firm's debt performance, Strategic Management Journal, 23.7, pp.595-618.

Uzzi, B. and Lancaster, R., 2003, Relational embeddedness and learning: The case of bank loan managers and their clients, Management Science, 49.4, pp.383-399.

Meet the Author:

Ramin Vandaie is a graduate student and researcher at The George Washington

University’s School of Business. He holds a BSc and MSc in Mechanical Engineering

and has several years of industry and academic work experience. Contact: 510,

21st NW, Apt. 404, Washington, DC, 2006,