On The Use Of

A Diagnostic Tool For Knowledge Audits

Ravi

Sharma1, Naguib Chowdhury², Nanyang Technological University, Singapore¹

, PETRONAS, Malaysia²

ABSTRACT:

The research reported in this paper outlines the

construction and utilisation of a diagnostic tool for

performing what we call a material knowledge audit in an enterprise of medium

complexity. The tool was developed by

adapting some of the more applicable techniques suggested in the literature by

practitioners. It was then put on trial

in five organisations – a library, an IT

consulting firm, a research institute, a telecommunications service provider,

and a media agency – which were involved in knowledge intensive business

activities. The appendices list the

three main components of such a field trial-ed

diagnostic instrument. Our

investigations revealed the dearth of such diagnostic tools as well as the need

to continually refine knowledge audit techniques so that the practice evolves

from an art into a science.

Keywords: Strategic alignment, Gap analysis,

Knowledge mapping

1. Overview Of Knowledge Audits

Knowledge, as compared to information, in the modern organization has elements of variety and is incongruous and heterogeneous in nature. In academic research as well as trade forums, the understanding of what constitutes knowledge is often debated because of the multidimensionality associated with it (cf. Feldman & Sherman 2001). Only when the knowledge is captured and organised into proper formats, can it be made accessible and put to further use. In effect, capturing knowledge is of little use if it is not organised in such a way that it can be understood, indexed, accessed easily, cross-referenced, searched, linked, and generally manipulated for maximum benefit of all members of an enterprise. Hence the capture, storage, transfer and exploitation of knowledge plays a critical role throughout the knowledge cycle and the cost of not retrieving it is indeed high (Gantz 2007). Indeed the capability of an organisation to create new knowledge, disseminate it throughout the organisation and embody it in its products, services and systems is defined by Nonaka & Takeuchi (1995) as an essential aspect of knowledge management (KM).

But as Peter Drucker famously said: “We cannot manage what we do not know how to measure!” A Knowledge Audit (K-Audit) is hence a systematic examination and evaluation of organizational knowledge health, which looks at whether knowledge is exploited when needed. More specifically, it is an analysis of the organization’s knowledge needs, existing knowledge assets or resources, knowledge flows, future knowledge needs, knowledge gaps, and finally, the behavior of people in sharing and creating knowledge. In one way, a knowledge audit can reveal an organization’s knowledge strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats and risks (Cheung et al. 2007; Hylton 2002; Liebowitz et al. 2000; Schikkard & Toit 2004). A K-Audit, typically, also includes an examination of organization’s strategy, leadership, collaborative, learning culture, technology infrastructure in its various knowledge processes.

In order to transform an organization to a learning and development mode and ensure an effective knowledge management strategy, a K-Audit is conducted, which will provide a current state of knowledge capability of the organization and a direction of where and how to improve that capability in order to be competitive in this fast changing knowledge era (Zack 1999). This is in effect the biggest challenge to conducting such an audit (Liebowitz et al. 2002; NLH 2005) – when it involves identifying what knowledge is needed, what knowledge already exists, where the gaps lie, who needs the knowledge, and how it will be used.

We call this an exhaustive K-Audit when it involves an assessment of how the sum of explicit as well as tacit knowledge within an organisation is exploited throughout the knowledge-cycle and the people and business processes add to such knowledge (Hylton, 2002). When a K-Audit is more results-oriented and entails determining the organization's effectiveness and efficiency of knowledge capture, codification, and transfer in the key business processes (Liebowitz et al., 2000), we call it a material K-Audit. As Prabha et al (2007) point out, there is an information satisficing behaviour inherent in the organisation that tends to preclude a comprehensive, all-encompassing search on account that the effort may not be justifiable. Both exhaustive as well as material K-Audits therefore check the health status of knowledge asset and its utilization in an organization and provides the framework for the audited unit to gain measured knowledge of its existing and potential knowledge value. However, whereas an exhaustive audit involves considerable amounts of time and resources in order to achieve a definitive outcome (say for the purpose of an M&A or creating the first instance of a corporate knowledge inventory), a material audit (as with the use of the term in accounting) only looks at key business processes that lead to an identifiable impact of interest (for example, an audit of knowledge flows in the pricing decisions of new products might look at how knowledge is shared between product development, contract manufacturing, marketing and finance in this key business process). Thomas Stewart in “The Case against Knowledge Management” (cited in Foo & Sharma 2007), pointed out that companies waste billions on knowledge management because they fail to figure out what knowledge they need, or how to manage it in the context of application. It takes little imagination to work out that a knowledge audit would provide an evidence-based approach to help companies or organizations ‘figure out what knowledge they need, and how to manage it’. This was the motivation for the present research.

Conducting K-Audits is an important aspect of not just KM but also for the strategic planning, both on the enterprise and business-unit levels, to sustain competitive advantages. Hylton (2002) more formally states that: “The knowledge audit process involves a thorough investigation, examination and analysis of the entire ‘life-cycle’ of corporate knowledge: what knowledge exists and where it is, where and how it is being created and who owns it. It measures and assesses the level of efficiency of knowledge flow. From knowledge creation and capture, to storage and access, to use and dissemination, to knowledge sharing and even knowledge disposal, when the organisation is no longer in need of particular elements of explicit or codified knowledge. With respect to people, the K-Audit measures the efficiency of transfer of tacit knowledge skills, when particular skills or expertise is no longer needed.” It is hence the KM equivalent of the requirements determination phase undertaken during traditional systems analysis and design. This is a necessary first step which leads to the creation of a knowledge map - a visual representation of an organisation’s knowledge. Technically, a knowledge map is a logical abstraction of a corporate taxonomy (which includes implementation details) and it reveals possible answers to the key questions of a K-Audit.

There are two recommended approaches to knowledge mapping (NLH 2005): i) map knowledge resources and assets, showing what knowledge exists in the organisation and where it can be found; and ii) include knowledge flows, showing how that knowledge moves around the organisation from source to target. In both cases, the key is a diagrammatic schemata of corporate knowledge of the explicit as well as tacit nature and an accompanying realisation of the value-added during the course of the knowledge flows.

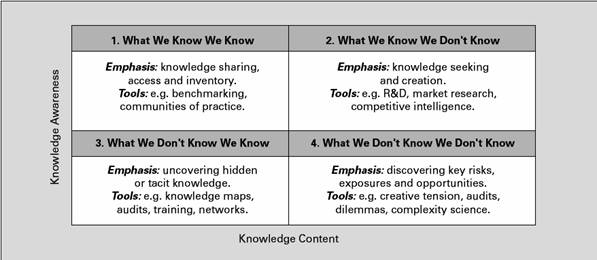

Building a knowledge map looks deceptively simple but perhaps requires more effort and resources than any other phase of developing a corporate taxonomy. It is a profound, soul-search that involves the highest level of strategic management and domain expertise to make judgments on fundamental business and knowledge strategies. Drawing from Drew (1999) “Boston Box” of four quadrants of analysis for a complete coverage of an organisation’s knowledge capital.

Figure 1: The Four Quadrants Of

The “

1. Quadrant 1 asks what the available knowledge resources such as stores (explicit knowledge resources) and expertise (tacit knowledge resources) are. In other words, the core competencies of the organization.

2. Quadrant 3 addresses the unexploited seepage in its knowledge capital repository – typically, hidden and undercapitalized resources, key leverage points in learning and development, and best practices perfected by certain departments.

3. Quadrant 2 takes the organizational learning impetus which seeks to position the organization to execute its strategic plans for growth. These are known gaps ascertained by benchmarking key performance indicators (eg quality, price, market share, innovation, brand name) and Competitive Intelligence of new R&D and innovation against competitors to determine competitive disadvantage.

4. Quadrant 4 refers to the blind spot of hidden opportunities and threats that may not be (as yet) apparent within the organisation’s leadership. Knowledge resources required to meet strategic objectives may not be available perhaps due to blocks in knowledge flows and networks and gaps and unmet needs for knowledge.

Daunting as this analysis may seem, is not a paradigm shift. The point being made is that the organisation of knowledge in the form of a K-Map carries with it criteria for evaluating possible gaps as well as leaks that need to be plugged. Drew (op. cit.) had captured some of these issues for some time now and the KM community has since developed an entire repertoire of tools for each of these quadrants (cf. Foo et al. 2007 for a textbook coverage of many of these tools).

2. Diagnostic Framework For A K-Audit

There is no universally accepted approach to conducting a K-audit - although a number of approaches have been developed such as stock or inventory-taking techniques; mapping of knowledge flows and networks; and mapping of knowledge resources (cf. KeKma; NLH 2005; KnowMap). The choice of approach depends on the business needs and objectives of the context. Regardless of the approach used, there are common instruments such as site observation, interviews, questionnaires, focus group, and workshops that may be applied. But there are issues and challenges facing their validity, reliability, replicability and usability in the field. The problems with using direct questions have been well discussed by Snowden (2003) - “They seek(s) answers within the expectation of the enquirer (K-auditor) and can not reveal hints and signs that fall outside his sphere of perception. They also ignore the context in which the knowledge is used. Things that work in a particular situation may not work in another scenario. Although asking indirect questions may eliminate this problem, how to phrase and frame the questions is critical to the audit result”. Hence it is imperative to establish a sequence of steps for a generically applicable K-Audit Tools which leads to a consistency of diagnosis.

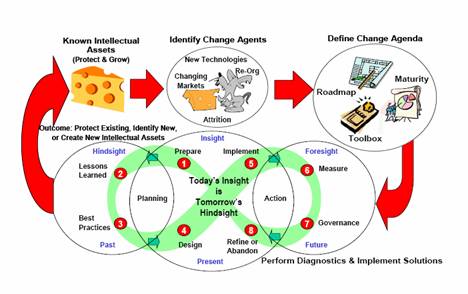

Figure 2: CIKM’s Frid Framework. (www.cikm.com)

The Canadian Institute of Knowledge Management has proposed a FRID Framework that may be used to analyse gaps in knowledge stores and flows. Equally important, the framework also helps define the diagnostic changes that need to be made in order to address any gaps. In this sense, the term ‘knowledge audit’ is in some ways a bit of a misnomer, since the traditional concept of an audit is to check performance against standard processes and report any material variances, as in financial auditing. A K-Audit is a more of a qualitative evaluation. It is essentially a sound investigation into an organisation’s knowledge ‘health’ and the use of the Frid Framework helps focus on:

¨ What are the organisation’s knowledge needs?

¨ What knowledge assets or resources does it have and where are they?

¨ What gaps exist in its knowledge?

¨ How does knowledge flow around the organisation?

¨ What blockages are there to that flow e.g. to what extent do its people, processes and technology currently support or hamper the effective flow of knowledge?

And more strategically:

¨ How is the organisation’s knowledge creation, sharing and re-use when benchmarked against competitors or best practices?

¨ What are the flows that lead it to becoming a sustainable learning organisation and in so doing helps it stay ahead of the curve?

The result of such an intense diagnostic

examination is that the K-audit helps an organization to clearly identify what

knowledge is needed to support overall organizational goals and individual and

team activities. It gives tangible evidence of the extent to which knowledge is

being effectively managed and indicates where improvements are needed. It explains how knowledge moves around in,

and is used by, that organization. It

provides a map of what knowledge exists in the organization and where it exists,

revealing both gaps and duplication. It

provides an inventory of knowledge assets, allowing them to become more visible

and therefore more measurable and accountable. It provides vital information

for the development of effective knowledge management programmes

and initiatives that are directly relevant to the organization’s specific

knowledge needs and current situation.

It helps in leveraging customer knowledge.

3. A Synthesis Of

Principal Components

Drawing from the theories of Duffy’s KM Readiness Assessments,

Holt’s extensive review of the literature on change management (both of

which are covered in Foo et al. 2007) and the

experience of multiple groups of practitioners (Hylton

2002; KnowMap; Liebowitz et al.

2000; NLH 2005) and in concert with a graduate student colloquium in knowledge

strategies, we constructed the K-Audit tools and deployment method to be

described in this section. However, as

the discerning reader will appreciate, this was not as “clean” as

it appears; both the diagnostic tools as well as methods were subject to

iterative refinements suggested by practitioners during the field trials. Nevertheless, the consensus arising from all

the above activities was that the K-audit should be divided into components or

activities which result in a milestone for the purpose of diagnostics and

corrective measures. For our present purpose of developing and utilising a diagnostic tool, we have defined a K-Audit with the following components which are ideally

performed in sequence):

¨ Knowledge Needs analysis

¨ Knowledge Inventory analysis

¨ Knowledge Flow analysis

¨

Knowledge Mapping

Figure 3: Principal Components Of A K-Audit.

The sequence of these components is consistent with the generalised knowledge life-cycle suggested by Birkenshaw and Sheehan (2002) which hence support a view of knowledge creation and re-use as the fundamental goals of KM per se.

3.1. Knowledge Needs Analysis (K-Needs

Analysis)

The major goal of this task is to identify

precisely what knowledge the organization, its people and team possess

currently and what knowledge they would require in the future in order to meet

their objectives and goals. Knowledge need analysis can help any organization

to develop its future strategy. Tiwana (2002)

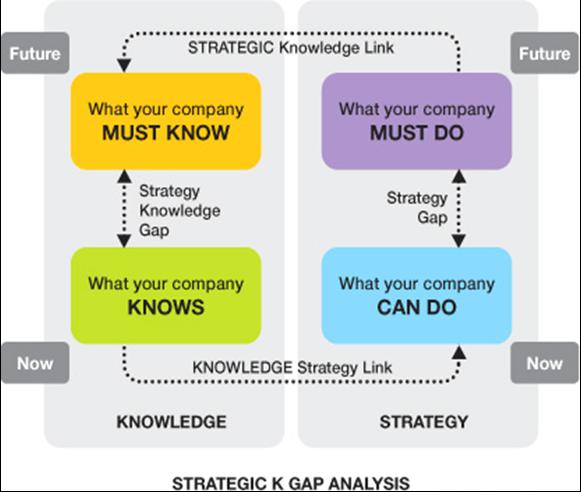

suggested the following to explain the Knowledge-Strategy Link:

Figure 4: Knowledge –

Strategy Gap Analysis; Tiwana (2002)

The K-need analysis should ideally also measure staff skills and competency enhancement-needs and opportunities for training and development, corporate knowledge culture-practices such as knowledge sharing attitude, collaboration, team spirit, rewards and recognitions & staff relationship with their superiors, peers and subordinates. An instance of the field instrument that supports this aspect of the K-Audit is shown in Appendix I. The deliverable or milestone is typically a presentation to management outlining any current gaps in knowledge and any future misalignment with strategy.

3.2. Knowledge Inventory

Analysis (K-Inventory Analysis)

Knowledge inventory is a knowledge stock-taking to identify and locate knowledge assets and resources throughout the entire organization. This process involves counting, indexing, and categorizing of corporate tacit and explicit knowledge. Knowledge inventory analysis comprises of 2 entities: Physical (Explicit) Knowledge inventory and Corporate Experts (sources of tacit knowledge) inventory.

¨

The Physical (Explicit) Knowledge inventory of an organization

includes:

§ Numbers, types and categories of documents, databases, libraries, intranet websites, links and subscriptions to external resources

§ Knowledge locations in the organization, and in its various systems

§ The organization and access of the knowledge (how knowledge resources are organized and how easy is it for people to find and access them)

§ Purpose, relevance and quality of knowledge (why do these resources exist, and how relevant and appropriate they are for that purpose, are they of good quality - up to date, reliable, evidence based, making sense, relevance to the organization)

§ Usage of the knowledge (are they actually being used by whom, when, what for and how often)

¨

The Corporate Experts (sources of Tacit Knowledge) inventory includes:

§ Staff directory and their academic and professional qualifications, skill & core competency levels and experience

§ Training and learning opportunities

§ Future potentials-leadership potential

¨

External contacts of staff includes:

§ Other than their personal info, training, learning opportunities (eg. scanning the business cards of the staff and tag them with their personal profile)

The K-inventory analysis may involve a series of surveys and interviews in order to get relevant answers to the above questions on both tacit and explicit knowledge that an organization may hold and have. By making comparisons between the knowledge inventory and the earlier analysis of knowledge needs, an organization will be able to identify gaps in their organization’s knowledge as well as areas of unnecessary duplication. Appendices II and III show the structured instrument that could be used to determine the explicit and tacit knowledge stores in order to determine the levels of codification versus personalization as defined by Hansen et al. (1999). It is usual at this stage to derive a rough K-Map as suggested by Grey (1999) or Conway & Sligar (2002), if it does not already exist, which shows how these stocks are organized and what may be in the 4 quadrants referred to by Drew (1999). Hence the milestone from this component is a rough K-Map of the gaps in explicit and tacit stores.

3.3. Knowledge Flows Analysis

(K-Flows Analysis)

Knowledge stores however are only one aspect of an organisation’s Intellectual Capital. The manner in which such knowledge flows in order to be exploited represents an intriguing aspect of what is known as Structural Capital (cf. Foo et al, 2007). Knowledge flow analysis looks at how knowledge resources move around the organization, from where it is to where it is needed. In other words, it is used to determine how people in an organization find the knowledge they need, and how do they share the knowledge they have, and some of the barriers to effective flows (Gupta and Govinderajan, 2000). Such an analysis looks at people, processes and systems:

Analysis of people: examine their attitude towards, habits and behaviors concerning, and skills in knowledge sharing, use and dissemination; it would be good to know the informal networks people build in the organization (eg. social networks of buddies within the organisation) since it is repeatedly observed that people tend to seek information from their group of friends in the organization. A Social Network Analysis can trace such informal knowledge flows.

Analysis of process: examine how people go about their daily work activities and how knowledge seeking, sharing, use and dissemination form parts of those activities, existence of policies and practices concerning flow, sharing and usage of information and knowledge, for example, are there any existing policies such as on information handling, management of records, web publishing etc? Or are there other policies that exist that may directly or indirectly affect or relate to knowledge management, which may act as enablers or barriers to a good knowledge practice?

Analysis of the system: examine technical infrastructure; for example, information technology systems, portals, content management, accessibility and ease of use, and current level of usage. To what extent do those existing systems facilitate knowledge sharing and flows, and help to connect people within the organization.

An analysis of knowledge flows allows an organization to further identify gaps in their organization’s knowledge and areas of duplication; it also highlights examples of good practice that can be built on, as well as blockages and barriers to knowledge flows and effective use. It will show where an organization needs to focus attention in their knowledge management initiatives in order to get knowledge moving from where it is to where it is needed. It is common to express these flows in the form of a graphic construct known as a social network (cf. Davenport & Prusak 1998). However, social network analysis is more than knowledge flows, it also captures who initiated a knowledge request, through whom, and how frequently. Nevertheless, the deliverable from this component of a K-Audit is a graphical notation of knowledge flows for various key business processes within the organisation.

3.4. Knowledge Mapping

(K-Mapping)

Recall that the K-Map is a navigation aid to explicit (codified) information and tacit knowledge, showing the importance and the relationships between knowledge stores and the dynamics of knowledge creation and storage. a detailed (as opposed to the rough) K-Map portrays the sources, flows, constraints and sinks (losses or stopping points) of knowledge within an organization. There are two main approaches to knowledge mapping:

i. Mapping knowledge assets and resources wherein the map shows what knowledge exists in the organization and where it can be found (holders of the knowledge-knowledge creator, collector, connector, users and knowledge critics, data repositories)

ii. Mapping knowledge flows where the map shows how knowledge moves around the organization from where it is to where it is needed.

In either case, the end deliverable of a visual representation that shows the Boston Box of 4 quadrants of knowledge assets is the outcome of K-Mapping.

An additional note about creating K-Maps is that since it is a visual representation of an organisation’s knowledge, the second approach provides the most complete picture for the knowledge auditor. However, the first is also useful, and in some organizations is made available to all staff to help people locate the knowledge they need.

4. Field Trials

The K-Audit diagnostic tool and deployment method that was formulated was

next subject to five field trials in order to determine their validity,

consistency, usefulness and ease of use.

The authors and three other graduate students in the practice-oriented M.Sc. in Knowledge Management programme

at the

It had been the consensus among practitioners (cf. Liebowitz

2000; NLH 2005; KnowMap) that common approaches and

tools that can be applied to conduct a knowledge audit are: site observation,

questionnaire-based surveys, face to face interviews, focus group discussions,

and workshops. Detailed site

examinations of corporate intranets are frequently part of this process

(Williamson 1997). A knowledge audit

should also be divided into four iterative stages: background study, data

collection, data analysis and data evaluation. The output of he deliverables of a knowledge

audit would be: a list of knowledge items (K-needs & current K-assets) in

the form of spreadsheets; a knowledge network map which shows the flow of

knowledge items; and social network map that reveals the interaction among

staff on knowledge sharing. In an early

stage, it must be clearly ascertained as to whether it was an exhaustive or

material K-Audit that was to be conducted.

The diagnostic tool suggested in this paper was found to be consistent

with such expectations among practitioners and hence useful. Moreover, training the graduate students on

its use proved to be effective after a 2-hour workshop. We next attempted to determine its validity

and consistency in the field.

1. Kick Off

Workshop. 1.1 Determining the Alignment of

Business and Knowledge Strategies 1.2 Communicating Scope and

Objectives of the KM Transformation Roadmap; Securing Management Buy-in 2. High Level KM

Self Assessment. 2.1 Design of Survey Instruments 2.2 Identification and Interview

of Knowledge Champions 2.3 Data Collection of Knowledge

Sources, Targets, Flows and Absorptive Capacity 3. Analysis of

Diagnostic Results. 3.1 Identification of gaps in

knowledge capture 3.2 Identification of gaps in

knowledge mobilization 3.3 KM Maturity Assessment 3.4 Development of Knowledge

Benefits Tree 4. Recommendations

for KM Transformation Roadmap 4.1 Focus Group Session and

Validation 4.2 Formal Report

Table 1: Typical K-Audit Field

Trial

Table 1 above shows the schedule of activities conducted at each of the five field trial sites which agreed to participate in the research with the assurance of confidentiality as well as the promise of sharing the diagnostic results. For the purpose of not expending undue resources, we agreed that the scope of the field trial would be a material audit of the major key business process that the participating client wished to assess – ie. the most significant “pain point”. Typically, first contact was made by telephone and after the scope of the material K-Audit was agreed upon, a Non-Disclosure and Copyright Agreement was executed. The field trial then moved to the first step – the kick-off workshop. Here, executive commitment was the key and the entire team was involved with the client to ascertain the level of support from management. Convincing key executives and training client representatives were the intended outcomes. In step two, client representatives drawn from IT, professional as well as support staff were roped in to customize the diagnostic instruments and trained to capture the required data at random intervals during a 3-4 month period. Here it was found that 30-40 minutes served as the threshold of tolerance for the task and that the responses had to be collected after each exercise in order to prevent a bias for repetitive assessments. While the knowledge needs and flows survey was self administered by emailing an online version to important nodes in the key business process, the “stack taking” of physical (codified) and human (tacit) knowledge assets were indeed more laborious and required an expert interplay of logistical as well as communications skills on the part of the client representatives driving the K-Audit at their respective sits. Step three proved to be the most challenging and involved considerable thought on generalizing the K-Maps and K-Flows obtained as well as the responses from various stakeholders in iterative follow-on sessions with the researchers which also involved considerable on site observations of work processes, record reviews of forms, reports and other documents, and (re-)interviewing key people. It was apparent that any statistical analysis (even the most basic of descriptive tabulations) would be meaningless (and perhaps even detrimental because of the alarm it would raise within the organisation about how these were to be used). Instead the emphasis was on comparative analyses of trends, patterns and intents and the over-riding question was whether the current knowledge assets and flows achived a satisfactory level of performance in the selected key business process.

A correspondence between the diagnosis from step three and a commonly utilized maturity model for knowledge management was derived. The 5iKM3 Framework proposed by Mohanty & Chand (2005) was found to be particularly useful (over other industry models such as APQC’s KMAT, SEI’s CMM, or variations from IBM, Infosys and the like) particularly because of its rich descriptions of the required maturity in each knowledge process. This is shown in Table 2 below.

|

|

Initial |

Intent |

Initiative |

Intelligent |

Innovative |

|

Create |

Knowledge creation is done but not acknowledged |

Knowledge creation is acknowledged and there is an effort to channel

the same |

Knowledge creation is given a thrust |

There is no opportunity lost in the knowledge creation |

Knowledge creation is a joy |

|

Capture |

There are no formal processes for the capture of knowledge or the

capture of knowledge is overlooked |

There is an effort to capture the knowledge but there is no formal

process |

There is a defined process to capture the knowledge at various

touch-points though they may not be exhaustive |

The capture processes are well in place and all touch-points are

being addressed effectively |

Capture processes are well integrated in the business processes |

|

Organise |

There is no formal structure to organise the accumulated knowledge |

There is no formal process |

There are defined processes to organise and store the knowledge in a

structured way |

The knowledge is well organised to cater to all types of needs |

Organisation of knowledge assets is optimised |

|

Store |

Is ad hoc and based on elementary tools |

There are some defined repositories but based on elementary tools |

There is a logical central repository and process based access |

The storage is well defined and available for access from anywhere

anytime |

Storage follows anything, anytime, anywhere paradigm |

|

(Re-)Use |

Is accidental |

There are problems in locating the knowledge at the right time |

There is a defined process and tools available for the use/reuse of

the knowledge |

Use/reuse scenarios are well articulated |

Use/reuse of knowledge is a culture |

Table 2: Knowledge Management Maturity and Assessment; Tata

Consultancy Services 5iKM3 Framework (Mohanty & Chand 2005)

The validity of our K-Audit approach to

practitioners in the field was primarily adjudged by the deliverables that will

help the client organization in identifying the gap between “what

is” at present and “what should be” in the future from a KM

perspective. Moreover, clients also

appreciated the iterative opportunities to take various snap-shots of the

knowledge stocks and flows. There was

often disagreement of what was as well as what should have been. Deliverables such as rough K-Maps, the Boston

Box, social networks and the final form K-Maps proved as invaluable

communication as well as clarification aids in articulating to management the

state of the knowledge strategy and its alignment with business strategy. The KM maturity model yielded insights on how

far ahead or lagging behind various the five KM processes (create, capture,

organize, store, re-use) were. Hence

there was strong acceptance of the KM Transformation Roadmap (ie. the required change management) that resulted from the

exercise for that key business process.

This was equally attributed to the methodology as well as analysis. The net result of such a material K-Audit was

a diagnostic indication of what steps needed to be taken in order to achieve a

desired outcome in knowledge creation and re-use. In many instances, this was had more to do

with Human Capital to Structural Capital conversion through the establishment

of a community of practice, coaching and mentoring schemes, and promoting

active learning opportunities than technology fixes such as creating intranet

knowledge repositories, directories or taxonomies.

It was clear however, that knowledge auditing very

much remains an art rather than a science, particularly the derivation of a

K-Map and the determination of gaps and leakages from the Boston Box. It was never seen as a quick or simple

process, and so the time and effort required will always need to be justified

by a clear return on investment. The

heuristic that around 80% of an organisation’s

value is tacit knowledge is indeed a stark reminder against focusing too much

time and energy on explicit knowledge and not enough on tacit knowledge. The ease or difficulty in collecting data for

the K-Audit is often a good indicator of the status of current knowledge

management practices – in other words, the more haphazard the KM

practices, the harder it will be to K-Map or K-Audit. And finally, while it may be appealing to outsource

the K-Audit to a consultant, the lesson from our field trials was that the

responses are more valid and accurate when harvested by internal (context

aware) sources.

Pepper (2000) had suggested a more formal model using concepts of topic, occurrence, association, identity,

facets and scope as diagnostic dimensions for organizational K-Maps but as yet

these have not been developed more fully. Nevertheless, the onus is on the all

stakeholders to grow and learn with usage and help refine the vocabulary,

metadata, clusters and may be a need to re-design and re-classify (and perhaps

use a new selection of meta-data) in order that the corporate knowledge base

continues to serve the organisation. At times, there may even be a need to

re-architect and migrate to other (more appropriate) business processes and

systems solutions. In all such cases,

diagnostics help ensure that knowledge remains a competitive weapon for the organisation rather than a legacy albatross.

In closing, the information overload problem has made it difficult for many knowledge professionals to find relevant and up-to-date information on the web, corporate databases or other digital repositories in order to be maximally effective in their work and make timely decisions. As a result, K-Audits have become an important part of the suite of tools to help ensure that users locate the knowledge that they need, when they need them, and if they are unavailable, someone is doing something about it. The K-Audit is potentially an authoritative intermediary that provides the terms and relationships an organisation will use in order to create, capture, organise, store, search, transfer and re-use its knowledge resources – explicit and tacit. Its return on investment should be an auditable improvement in the organisation’s knowledge management.

5. Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to their

graduate assistants Mervyn Chia

and Padideh Moghadam, and

colleagues, Miguel Arroyo and Margaret Tan, for their thoughtful

contributions. Many thanks are also due

to the participating practitioners for their useful insights and feedback.

6. References

Birkinshaw, J. and Sheehan, T. (2002), "Managing the Knowledge Life

Cycle", MIT Sloan Management Review, Fall,

75-83.

C.F. Cheung, M.L. Li, W.Y. Shek,

W.B. Lee and T.S. Tsang (2007). “A systematic approach for knowledge auditing: a case study

in transportation sector” Journal

of Knowledge Management 11 (4) 140- 158.

Conway, S. and Sligar, C.

(2002). Unlocking Knowledge Assets. Quantum Books,

Drew S. (1999). “Building Knowledge

Management into Strategy: Making Sense of a New Perspective.” Long Range Planning, 32 (1) 130-136.

Feldman, S. and Sherman, C. (2001). The High Cost of Not Finding Information. An IDC White Paper available at http://www.idc.com.

Foo, S., Sharma, R. and Chua, A. (2007). Knowledge

Management Tools and Techniques, Prentice

Gantz, J.F. (Project Director). (2007).

Expanding Digital Universe: A Forecast of Worldwide Information

Growth Through 2010. IDC White Paper. Available at : www.emc.com/about/destination/digital_universe accessed on

22-May-07.

Grey, D. (1999). Knowledge Mapping: a practical overview. Smith Weaver Smith online article. Available at : http://www.smithweaversmith.com/knowledg2.htm accessed on 22-May-07.

Gupta, A. K. and Govindarajan,

V. (2000). Knowledge flows within multinational

corporations. Strategic

Management Journal. 21, 473-496.

Hansen M., Nohria

N., and Tierney T. (1999). “What’s

your strategy for managing knowledge”, Harvard Business Review, March-April,

106-116.

Hylton, A. (2002). Measuring & Assessing Knowledge-Value & the Pivotal Role of the Knowledge Audit. Available at : http://www.providersedge.com/docs/km_articles/Measuring_&_Assessing_K-Value_&_Pivotal_Role_of_K-Audit.pdf accessed on 22-May-07.

KeKma-Audit, KeKma-Audit, Knowledge audit & KM, from http://www.kekma-audit.com/index.htm

Know Map – the KM, Auditing and Mapping

magazine, Toolkit: Auditing. Available at : http://www.knowmap.com/current_contents/toolkit_auditing.html

accessed on 22-May-07.

Liebowitz, J., Rubenstein-Montano, B., McCaw, D., Buchwalter, J., Browning, C., Newman, B. (2000). The Knowledge Audit. Knowledge and Process Management, 7 (1), 3-10. Online version available at: http://www.library.nhs.uk/knowledgemanagement/ViewResource.aspx?resID=251510&tabID=289 accessed on 22-May-07.

Mohanty, S. and Chand, M. (2005). “5iKM3 Knowledge Management Maturity Model”. Tata Consulting Services White Paper. Avaliable at : http://www.tcs.com/NAndI/default1.aspx?Cat_Id=7&DocType=324&docid=419 accessed on 22-May-07.

National Library for Health (NLH) KM Specialist Library. (2005). Conducting a knowledge audit by C De Brun. Available at : http://www.library.nhs.uk/knowledgemanagement/ViewResource.aspx?resID=93807&tabID=290 accessed on 22-May-07.

Nonaka, I. and Takeuchi, H.

(1995), The Knowledge Creating Company,

Pepper, S. (2000). “The TAO of Topic Maps.” Presented at XML Europe

2000.

Prabha, C., Connaway, L.S., Olszewski, L. and Jenkins, L.R. (2007). “What is enough? Satisficing information needs.” Journal of Documentation, 63 (1), 74-89. Pre-print available at: http://www.oclc.org/research/publications/ archive/2007/prabha-satisficing.pdf accessed on 22-May-07.

Schwikkard, D.B., and du Toit, A.S.A. (2004), “Analysing knowledge requirements: a case study”, Aslib Proceedings, 56 (2), 104-111.

Snowden, D. (2003). “Managing for serendipity or why we should lay off best practice in

KM”.

Tiwana, A. (2002), The knowledge management toolkit: Orchestrating IT, Strategy and Knowledge Platforms, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Williamson, N. J. (1997). “Knowledge structures and

the Internet.” Knowledge Organisation

for Information Retrieval: Proceedings of the 6th International

Study Conference on the Classification Research,

Zack, M.H. (1999), “Developing a Knowledge

Strategy”,

Appendix I

Knowledge

Needs / Knowledge-Flow Analysis Diagnosis

Major

goal – Identify the current

and the future knowledge needs as well as how knowledge flows in an

organization

|

|

Current |

Future |

|

|

Organization- Overall |

Exists |

Required |

Required |

|

Functions |

|

|

|

|

Key Deliverables |

|

|

|

|

Core competencies |

|

|

|

|

|

Current |

Future |

|

|

Organization- Division |

Exists |

Required |

Required |

|

Functions |

|

|

|

|

Key Deliverables |

|

|

|

|

Core competencies |

|

|

|

|

|

Current |

Future |

|

|

Organization Division- Individual

Level |

Exists |

Required |

Required |

|

Types of

Knowledge |

|

|

|

|

Sources of

Knowledge |

|

|

|

|

Frequency of

usage |

|

|

|

|

Key

stakeholders |

|

|

|

|

Key

K-processes |

|

|

|

|

K-deliverables |

|

|

|

|

K-resources

sharing partners |

|

|

|

|

Time spend

in searching for knowledge |

|

|

|

Perception on Knowledge Sharing

|

No |

Area: The overall environment of my dept: |

Strongly agree |

Agree |

Neutral |

Disagree |

Strongly disagree |

|

1 |

·

facilitates knowledge creation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

·

facilitates knowledge storage/retrieval |

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 |

·

facilitates knowledge transfer |

|

|

|

|

|

|

4 |

·

enables me to accomplish tasks more quickly |

|

|

|

|

|

|

5 |

·

improves my job performance |

|

|

|

|

|

|

6 |

·

is useful in my job overall |

|

|

|

|

|

|

7 |

·

enables the organization to react more quickly to changes in the

marketplace |

|

|

|

|

|

|

8 |

·

speeds decision making |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Perception about

Knowledge in the organization… |

Strongly agree |

Agree |

Neutral |

Disagree |

Strongly disagree |

|

9 |

·

the specific knowledge that I need resides with the experts

rather than being stored in the portal because the knowledge is typically difficult

to clearly articulate |

|

|

|

|

|

|

10 |

·

the knowledge stored in the portal

cannot be directly applied without extensive modifications because of the

fast-paced, dynamic environment in which my department operates. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

11 |

·

as the tasks of my department change

frequently, I am always having to seek new knowledge that is not directly available

in the K-portal or databases. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

12 |

·

I am able to extensively reuse knowledge from the K-portal after

making few if any changes to adapt the retrieved knowledge to the current

situation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

13 |

·

the knowledge that I find in the K-portal can be directly

applied to current situations with little or no need to seek out or create

new knowledge |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Do you think the members of your

department are: |

Strongly agree |

Agree |

Neutral |

Disagree |

Strongly disagree |

|

14 |

·

satisfied by the degree of collaboration |

|

|

|

|

|

|

15 |

·

supportive for knowledge sharing & creation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

There is a willingness to: |

Strongly agree |

Agree |

Neutral |

Disagree |

Strongly disagree |

|

16 |

·

collaborate across organizational units within our organization |

|

|

|

|

|

|

17 |

·

accept responsibility for failure |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I always find: |

Strongly agree |

Agree |

Neutral |

Disagree |

Strongly disagree |

|

18 |

·

the precise knowledge I need |

|

|

|

|

|

|

19 |

·

sufficient knowledge to enable me to do my

tasks. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

20 |

·

I am satisfied with the knowledge that is available in my dept

to use |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

There should be reward system for |

Strongly agree |

Agree |

Neutral |

Disagree |

Strongly disagree |

|

21 |

·

creating reusable knowledge resources |

|

|

|

|

|

|

22 |

·

reusing existing knowledge resources |

|

|

|

|

|

|

23 |

·

contributing to a library of reusable knowledge resources |

|

|

|

|

|

Rate the responses

from 1 (least typical) to 5 (most typical)

1. When a colleague asks you

to help with their knowledge needs, what type of knowledge is typically sought?

a)

essential for business performance

________

b)

essential for the company’s competitive advantages ________

c)

important for leading to innovation and creative work ________

d)

outdated and no longer useful for the business ________

2. How did you

acquire most of the skills and expertise that you have been using in your job

over the past 6 months?

in this organization ___

through self learning ___

through formal training ___

at my last job or elsewhere ___

3. Where is

most of the knowledge that you need to do your work located or stored?

In paper-based documents ____

In our team/dept’s

member’s head ____

In our central information system ____

On my personal or workstation

computer/hard drive ____

4.

Knowledge that I acquire in my present job / organization, belongs

first and foremost to

Me alone ____

The company alone ____

Depends on how much I had put in to it ____

Both myself and the company ____

5.

How often do you make use of documented procedures to do your work

when you are stuck

Constantly _____

Very often _____

Quite often _____

Not often/rarely _____

6.

Which of the following is the biggest barrier to your being able

to store information you receive more efficiently and effectively

Lack of time/too busy _____

Poor tools/technology _____

Organization policy/directives _____

Poor information systems/processes _____

7.

How often do you share information with other departments in

formal way

Constantly _____

Very often _____

Quite often _____

Not often/rarely _____

8.

What are the challenges in sharing information with people from

other departments

Don’t perceive there is an urgent need to share _____

Lack of open-minded sharing environment _____

Lack of trust of other people’s knowledge _____

No proper organizational guidelines on sharing _____

Bureaucratic procedure involved in sharing info/knowledge _____

Task doesn’t require cross-dept. info sharing _____

No proper IT platform to share _____

Do not know about other person’s knowledge needs _____

Appendix II

Knowledge Inventory

Analysis (Physical Knowledge)

Major goal: to identify and locate knowledge

assets and resources throughout the entire organization.

|

|

Current |

Future |

|

|

Organization Division |

Exists |

Required |

Required |

|

No. of

databases |

|

|

|

|

No. of files

in the system |

|

|

|

|

ERP |

|

|

|

|

Primary

storage |

|

|

|

|

Decision

Support System |

|

|

|

|

Filing

system |

|

|

|

|

Groupware |

|

|

|

|

File sharing

with other departments |

|

|

|

|

Physical

file/report storage |

|

|

|

|

Archiving |

|

|

|

General

audit:

1.

Categories of knowledge available

2.

Total number of files

3.

Amount of new knowledge created by the

staff

4.

Number of new knowledge collected from

external sources

5.

Who are the owners of the various

knowledge

6.

Monthly knowledge creation

7.

Monthly knowledge contribution in the

portal

8.

Yearly statistics and comparative study

Appendix III

Knowledge Inventory

Analysis (Human Capital)

Major goal: to identify and locate internal

experts within the organization

|

|

Current |

Future |

|

|

Organization Division |

Exists |

Required |

Required |

|

Staff and

their expert areas |

|

|

|

|

Expert

Databases |

|

|

|

|

Staff

development plans |

|

|

|

|

Succession

Planning |

|

|

|

|

Training,

Coaching, Mentoring Incentives |

|

|

|

|

Performance

Appraisal System |

|

|

|

|

List of

ex-staff |

|

|

|

|

Database of

External Experts |

|

|

|

Scope of

audit:

- Expert categories

2.

Comparative analysis of staff placement

to their expertise

3.

Analysis of Expert database - existing vs.

future development

4.

Succession planning in the organization

5.

Knowledge capture of leaving experts-

any procedures exists? Plans?

6.

Development of external industry

experts – any databases?

7.

Plans for expert knowledge sharing on

regular basis

8.

Development of best practices using

experts

About the Authors:

Ravi Sharma is a professor in the

knowledge management programme of the