Competitive

Advantage Via A Culture Of Knowledge Management: Transferring Tacit Knowledge

Into Explicit

Salah Eldin Adam Hamza, SOFCON Consulting Engineering

Company, Saudi Arabia

ABSTRACT:

Competitive Advantage is more or less a dream if it is not closely tied to knowledge management; however many studies have noted that the challenge for knowledge management remains its tacit portion since by definition tacit knowledge is hard to articulate and transfer. This paper explores the notion that for competitive advantage, the transfer of tacit knowledge is essential to the integration of organizational knowledge within organizational areas such as people, processes and technology. The paper commences with principles, concepts and advances of knowledge management, and emphasizes previous attempts to transfer tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge management. Subsequently the paper presents an integrated and comprehensive, empirically tested model to argue that tacit knowledge can be transferred into explicit knowledge through a structured process of communication, interaction, collection and circulation in order to achieve competitive advantage.

Keywords: Competitive

advantage, Explicit knowledge, Knowledge management culture, Knowledge

management frameworks, Knowledge management models, Tacit knowledge

1.†††††††† Introduction

According to Birkinshaw and Sheehan (2002) and Teece (2000), effective knowledge management plays an increasingly important role in sustaining the competitive advantage of organizations in the new economy. It is worth noting that competitive advantage is brought about through developing and putting into effect innovative business solutions that recycle applicable knowledge, and that use newly formed knowledge.† This link between the management of knowledge and the development of a sustainable competitive advantage in modern organizations is not new, although, the focus on knowledge characteristics in general and the tacit portion of it, in particular, has increased within modern organizations, still there is a struggle in this area.

The more communication, involvement and interaction of people the more chance for organizations to expose tacit knowledge residing in individuals’ brains. Individuals maintaining good relationships are more likely to exchange tacit knowledge. Augier and Vendelu (1999) treated knowledge networks and concluded that tacit knowledge is best transmitted through personal relationships.† Several attempts have been made by organizations to tackle the organizational knowledge as it pertains to competitive advantage. They have identified that developing a society of employees who are open minded and free opinion may be a more wise approach than the acceptance of a total structure such as quality or knowledge management. On the contrary, organizations need to change to a strategy of attracting or developing whatever knowledge, capability and competencies relevant to the opportunities they define and the markets their imaginations create. In this context, Coulson-Thomas (1997, p. 26) stressed that:

“Boards should be learning and steering rather than planning and

implementing. At the frontier of exploration there may be little knowledge to

manage. The challenge may be one of discovery and innovation. Boards should

anticipate, support and enable. They should stress the fun of shared learning,

and of future discovery and creation, rather than dwell on the pain of past

restructuring.”

Individuals who are rich of tacit knowledge constitute a wealth of intangible asset to the organization. As long as they stay on employment with the organization, they continue playing a competitive figure through effective decision making, communication and contribution. Once employees leave an organization, knowledge in their heads is also gone. The problem is that in today’s business environment, there is a high turnover of human resources. The International Labor Organization (ILO) indicated high lack of decent work and recommended increasing the chances of finding decent jobs by providing effective re-employment services, counseling, training and financial incentives (ILO, 2007).

Many organizations have experimented and utilized various possible options of knowledge management systems including, but not limited to, technological-based solutions, information technology, bulletin boards, discussion forms, intranets and search engines. Several organizations have paid attention to tacit knowledge in particular, and utilized networks and cognitive frames in managing their corporate knowledge. Gupta and McDaniel (2002, p. 3) synthesized a framework with five necessary elements for creating successful knowledge management: “harvesting, filtering, configuration, dissemination, and application”. Gupta and McDaniel (2002) classified tacit knowledge as existing knowledge to be captured within the firm from inside the minds of its employees or from databases versus explicit knowledge that can be acquired from outside the company as new knowledge.

The basic problem associated with fluctuating organizational competitive advantage resides with lack of integrated and comprehensive system to create, document, circulate and update organizational knowledge in general and tacit knowledge in particular. This paper develops a framework that encompasses these aspects to bring about organizational competitive advantage and is organized as follows: in the next section we will discuss the main features of knowledge management approaches and argue each in the context of tacit management and its relation to create and maintain organizational competitive advantage; in the third section we will discuss and present an integrated and comprehensive model to argue that practice of tacit knowledge management is culturally based and if implemented in a structured manner will equip organizations with needed competitive advantage; at the end, the paper provides some conclusions for future research.

2.†††††††† Literature Review

2.1.††††† About Tacit Knowledge

The concept of tacit knowledge refers to knowledge which is only known by an individual and that is difficult to communicate to the rest of an organization. Knowledge that is easy to communicate is called explicit knowledge. The process of transforming tacit knowledge into explicit is known as codification or articulation, Birkinshaw (2001).

It has been found that tacit knowledge is a crucial input to the innovation process. A society’s ability to innovate depends on its level of tacit knowledge on how to innovate. Rebernik and Sirec (2007) emphasized that tacit knowledge may only be effective when embedded in a particular organizational culture, structure and set of processes and routines. The difficulty in copying tacit knowledge is why it forms the basis of a unique competitive advantage.† Polanyi (1983) suggested that scientific inquiry could not be reduced to facts, and that the search for new and novel research problems requires tacit knowledge about how to approach an unknown. Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995) brought the concept of tacit knowledge into the realm of corporate innovation and indicated that Japanese companies are more innovative because they are able to successfully collectivize individual tacit knowledge to the firm.

2.2.††††† Aspects Of Competitive

Advantage

Tacit knowledge can be managed through organization’s knowledge processes; including strategic planning, decision making, marketing and hiring personnel. Leitch and Rosen (2001) emphasized that understanding and optimizing knowledge management processes can offer organizations a competitive advantage regardless of their business sector. Moreover, Leitch and Rosen (2001, p. 10) indicated that several professionals, under the sponsorship of Knowledge Management Consortium International, had developed a Knowledge Life Cycle model of three-phases:

1. “Acquire information and unverified knowledge”,

2. “Produce new, validated knowledge from the acquired

information and unverified knowledge”,

3. “Integrate the new knowledge into the organization for

improved effectiveness”.

Business leaders understand the strategic significance of knowledge and the

need to manage knowledge assets. Nevertheless, their efforts fail to achieve

real goals for several causes: belief that acquisition of the right knowledge

automatically generates benefits, lack of focus on knowledge management

initiatives, relying on technology to provide solution and benefit, structures

that are inappropriate for capitalizing on an organization’s knowledge

assets and lack of proper ownership (

Aspects of organizational competitiveness may differ from small medium enterprises (SME) to large organizations. Bennett and Smith (2002) assessed the factors associated with the UK SME's competitive conditions and competitive advantage and confirmed that, as businesses expand, SME extend their strategy to seek specialization and differentiation of their products and services and diversification of their customer base. Oliver (1997) argued that an organization's sustainable advantage depends on its talent to manage the institutional framework of its resource decisions. That framework should include internal culture in addition to external influences from the government, society and inter-organization relations that describe communally satisfactory economic performance.

2.3.††††† Link Between Knowledge

Management And Competitive Advantage

For the last two decades, knowledge management has been a recognized discipline, and large organizations have acquired dedicated information technology and human resources accordingly. Recently, a rapid growth for the purpose of performance excellence and competitive advantage is clearly demonstrated by researchers who proposed methodologies for capturing and representing organizational management (Kim et al., 2003). In this regards, Kim et al. (2003, p. 44) argue that:

“Maintaining knowledge is more difficult than creating knowledge;

promotion of knowledge sharing culture is indispensable; top management support

on knowledge management project is inevitable; reward system is clearly

declared to enhance knowledge sharing; knowledge management system should

satisfy knowledge requirements”.

Though management executives trust that sustainable competitive advantage relies on the capacity to generate and utilize new knowledge, they still seek a structured universal approach for this purpose. Franken and Braganza (2006) discussed the assumptions of a standard knowledge management approach and showed that the choice of knowledge management approach must be closely aligned with the organization’s strategic and operational form in order to harvest the anticipated benefits. In this context, Franken and Braganza (2006, p. 18) concluded that:

®

“Prospector-type

organizations will tend to adopt bottom-up approaches for effective knowledge

creation”;

®

“Defender-type organizations

will tend to adopt top-down approaches”; and

®

“Analyzer types will

adopt middle-up-down knowledge creation approaches”.

Individuals usually carry in their minds a huge quantity of knowledge deemed to be useful to business but unfortunately not stated in an organizations’ procedures, policies and databases. Crawford (2005) iterates that tacit management is unstated knowledge in a person’s head that is habitually not easy to explain and convey and includes lessons learned, know-how, judgment, rules of thumb and intuition. Business studies conducted a few years ago revealed that tacit knowledge constitutes 42 percent of corporate organizational knowledge (Clarke and Rollo, 2001). This indicates that organizations without serious and well structured knowledge management systems that take care of tacit knowledge are missing basic business tools and are ill organized for achieving competitive advantage.

Tacit knowledge lies beneath many competitive capabilities. Experience, secured as tacit knowledge, habitually reaches perception in the form of intuitions, insights and lights of stimulation. The capacity of mind to make sense of past compilation of experiences and to connect patterns from the past to the present and future is essential to the innovation process. The inspiration necessary for innovation derives not only from evident and noticeable expertise, but from hidden supply of experience, Thus, tacit knowledge is unrevealed to competitors unless key individuals are hired away.

The talent to capture and exploit corporate knowledge has become vital for firms as they seek to adjust to changes in the business environment. Whether it be learning from past successes or failures, identifying opportunities to improve customer profitability, or simply enabling teams to become more productive, knowledge management lies at the heart of any well-managed organization. A study published by the Economist Intelligence Unit and sponsored by Tata Consultancy Services (The Economist, 2005, p. 2) reported the following findings that confirm relation of knowledge management to competitive advantage:

®

“Consolidating

information and providing consistent performance indicators are regarded as the

most important steps firms can take to improve the speed and quality of decision-making,”

®

“Firms are looking for IT

tools that allow employees to prioritize information, and to extract valuable

insights from an ocean of data. For most managers, having information that they

can quickly interpret and analyze is much more important than, for example,

having information on the move. There is also growing demand for smarter

management information systems, with tools like digital dashboards enabling

executives to track their firms’ key performance indicators on an almost

real-time basis,”

®

“Companies have

demonstrated how customer analytics can support initiatives to increase

customer loyalty and expand markets share, much to the embarrassment of their

competitors,”

®

“Understanding who knows

what, and how people use different types of information as part of their work,

is just as important a part of good knowledge management as having the latest

business intelligence technology”.

2.4.††††† Knowledge Management

Models And Frameworks

Organizations need to align their frameworks, structures and processes to a knowledge management strategy in order to realize the anticipated benefits of knowledge management. Literature recognizes that knowledge management strategies must follow competitive strategies for organizations to build up sustainable competitive advantages through utilization of exclusive knowledge resources (Hansen et al., 1999).

Soft measures of knowledge management, including but not limited to enhanced

collaboration, improved communication, improved employee skills and better

decision making, are believed to impact the success and effectiveness of

knowledge management. Anantatmula and Kanungo (2006) identified a set of

criteria to assess the effect of soft measures on knowledge management using

the

Franken and Braganza (2006) proposed a framework that puts the knowledge management models of Nonaka (1994) in context in relation to the strategic typology of Miles and Snow (1978). Franken and Braganza (2006) attempted to assemble Miles and Snow’s framework and Nonaka’s knowledge creation spiral and management models.

Bellini and Storto (2006, p. 154) conducted an explorative research on information and communication technology on small firms and proposed a framework relating growth strategies and knowledge structure. The model they developed showed that the knowledge structure profile affects the growth strategy performance of the organization. Further, their model indicated the following characteristics of small firm business growth in relation to competitive advantage:

®

“The negative impact of

increasing age of small firms could be explained by the progressive

obsolescence of the initial technical competences of the business

founder”,

®

“The low level of renewal

of the initial competences probably derives from their nature, strictly linked

to the previous educational, academic or professional activities of the

founders”,

®

“The best performances of

small firms underline the strategic relevance of the ability to integrate, on

the one hand, emotional and creative elements with an operative and intentional

rationale, and, on the other hand, marketing, business and technical

capabilities”, and

®

“The methodological

limits tied to the current use of a unique variable (turnover rate) to measure

the growth, because of the variegated aspects of this phenomenon”.

3.†††††††† Developing An Effective

Culture Of Tacit Knowledge Management – A Proposed Model

Organizations can be tempted to occupy a low risk, low reward position, exploiting and protecting existing stable products, processes and customers. This initially low-risk strategy evolves into high-risk strategy over time through competition driving the organization into selling capacity as a commodity. The organization can delay dropping out of the Paradigm Frame at this point by developing Key Account Management or partnership approaches to mask the decline in its products (Millman, 1993).† Organizations seeking competitive advantage must instead focus on capturing and utilizing tacit knowledge, as well as explicit knowledge. World class organizations see knowledge management as an undertaking around which all staff should congregate. They influence employees to embrace knowledge management and become involved in the goals and results it yields.

The most effective way to utilize tacit knowledge within the organization and to make it a tool for competitive advantage is through structured organizational behavior considering all areas of business operations in a consistent and objective manner. Recent studies reveal that best practice organizations link their knowledge management practice and results to their quality initiatives organization-wide. In his recent paper on benchmarking for best practice management, Hamza (2007a) recommended that organizational knowledge must be shared so decisions are made in the best interest of the company as a whole. This transforms each system from simply an “indicator of knowledge handling” to an “enabler of excellence”. It is therefore extremely important to note that tacit knowledge management should not be stressed as a separate activity but rather as an integrated approach to enhance organizational and managerial processes.

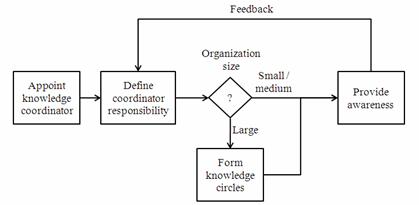

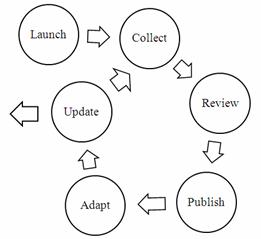

The road map presented by this paper is drawn from the best practices concluded from case study analysis. It is important to note that in most organizations there is no separate knowledge management system. This model therefore integrates knowledge management within the overall management process through establishing a culture of knowledge management as shown in Figure 1. The model consists of six steps that are meant to bring together all aspects of business excellence.

3.1.††††† Step 1: Launching

Hamza (2007b) indicated that for many organizations, especially in the

Figure 1: Culture of Knowledge Launching

To handle competition better, this step should consider integration of tacit knowledge management into business processes, right from the beginning, in order to help maintain leadership as a competitive advantage enabler.

Figure 2: Tacit Knowledge Management Framework

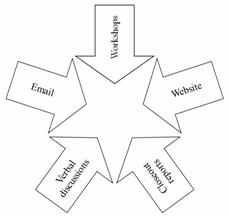

3.2.††††† Step 2: Collection

This is the most critical stage in the process of transferring tacit knowledge into explicit. It should be concerned with identifying, writing, and submitting tacit knowledge initiatives gained from experience, successful or otherwise, for the purpose of improving future performance. The organization needs to set means to stimulate employees thinking and development by identifying and aligning with knowledge necessary to support the organization’s strategy and operations to achieve the projected benefits. Further, organizations shall establish a knowledge base to enable their members to capitalize on verified successes and mistakes, thus producing a cutting edge competitive advantage. The collection process should be continuous throughout the life cycle of the organization. Figure 3 shows various aspects organizations may adopt for tacit knowledge collection depending on the nature and size of the organization.

Figure 3: Tacit Knowledge Collection

It is critical for the knowledge coordinator and knowledge circles to actively create a motivated and flexible environment by allowing and absorbing tacit knowledge sharing initiatives. Formal collection workshops can be arranged at regular intervals (based on organizational needs) to keep the organization on its toes in terms of continuous awareness, commitment and system update.

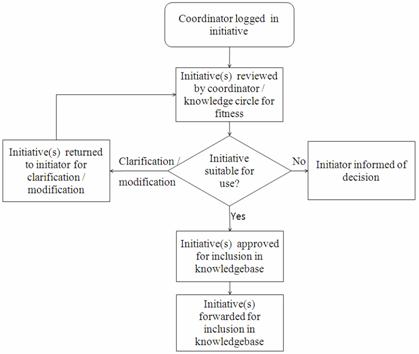

3.3.††††† Step 3: Reviewing

Irrespective of the collection source, the tacit knowledge initiative shall be thoroughly and promptly reviewed for fitness to business use. The organization needs to establish a formal review process for tacit knowledge initiatives. The outcome of this step could be one of the possibilities as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Tacit Knowledge Review

3.4.††††† Step 4: Publishing The

Tacit Knowledge Base

In order to ensure wider applicability and benefit, documented tacit knowledge must be published for a wider readership and usability within all organizational levels.

Disseminating knowledge is critical for world class organizations as an effective means of achieving and maintaining operational excellence and competitive advantage. Despite the help of information technology in online publishing, organizations still struggle with information management and dissemination, especially when trying to share vast amount of information. Nadeau, et al. (2004) presented the idea of how large organizations can plan to move towards greater coherence, bringing standards, tools and methodologies for information exchange. According to Obaide and Alshawi (2007, p. 14), “tacit knowledge is distributed and shared through formal and informal socialization. This takes place in the forms of sharing experiences, spending time with each other, apprenticeship, mentorship, meetings, Communities of Practice, brainstorming sessions and group-work technologies”. However, this paper emphasizes formal distribution and sharing through a structured model.

3.5.††††† Step 5: Adapt Tacit

Knowledge Into Daily Business Practices

The ultimate goal for collecting tacit knowledge is an effective and accurate adaptation for the right purpose, at the right situation and at the right time. Koh et al. (2005) emphasized that in order to increase the flexibility of the knowledge structure for accumulation and adaptation, a non-hierarchical knowledge structure is needed. Koh et al. (2005) also proposed a knowledge expression method to facilitate the rearrangement of design knowledge, to promote the flexibility of knowledge structure, and to evolve the creative knowledge from similar design. Nevertheless, organization members need to have skills and experience in order to adapt the knowledge they gain, and to generate benefit in developing a competitive advantage. It is important for organizations to grow knowledgeable staff through both developing existing employees and hiring new workforce. It is also imperative for the knowledge coordinator and knowledge circles to ensure progress of the implementation of collected knowledge, to facilitate the implementation process; and to provide guidance and training to other employees.

3.6.††††† Step 6: Update And Archive

Tacit Knowledge

Conveyance: individuals with greater tacit knowledge will possibly pass their knowledge to individuals lacking basic knowledge and skills through direct and indirect communication, interaction and involvement. In general, a significant amount of the transferred knowledge is also conveyed through face to face discussions, sharing ideas, consulting one another and instructing our subordinates.

4.†††††††† Conclusions

The proposed model discussed is competitive-advantage oriented. It presents a continuous process of tacit knowledge identification, collection and adaptation through endless business needs assessment. A key direction for future research will be to apply the model as discussed, and to evaluate its impact on addressing the development of organizational competitive advantage.

5.†††††††† References

Anantatmula, V. and Kanungo, S. (2006). Structuring the underlying relations among the knowledge management outcomes. Journal of Knowledge Management, 10 (4), 25-42.

Augier, M. and Vendelý, M.T. (1999). Networks, cognition and management of tacit knowledge. Journal of Knowledge Management, 3 (4), 252-261.

Bellini, E. and Storto, C.L. (2006). Growth strategy as practice in small firm as knowledge structure. International Journal of Knowledge Management Studies, 1 (1/2), 133-159.

Bennett, R.J. and Smith, C.

(2002). Competitive conditions, competitive advantage and the location of SMEs.

Journal of Small Business and

Birkinshaw, J. and Sheehan, T. (2002). Managing the knowledge life cycle. Sloan Management Review, 44 (1), 75–84.

Birkinshaw, J. (2001). Making sense of knowledge management. Ivey Business Journal, 65 (4), 32-36.

Clarke, T. and Rollo, C. (2001). Corporate initiatives in knowledge management. Education + Training, 43 (4-5), 206-214.

Collins, H.M. (2001). Tacit Knowledge, Trust and the Q of Sapphire. Social Studies of Science, 31 (1), 71-85.

Coulson-Thomas (1997). The Future of the Organization: Selected Knowledge Management Issues. The Journal of Knowledge Management, 1 (1), 15-26.

Crawford, C.B. (2005). Effects of transformational leadership and organizational position on knowledge management. Journal of Knowledge Management, 9 (6), 6-16.

Franken, A. and Braganza, A. (2006). Organizational forms and knowledge management: one size fits all? International Journal of Knowledge Management Studies, 1 (1/2), 18-37.

Gupta, A. and McDaniel, J. (2002). Creating Competitive Advantage By Effectively Managing Knowledge: A Framework for Knowledge Management. Journal of Knowledge Management Practice, 3 (2), 40-49.

Hamza, S.E.A. (2007a). Benchmarking for best practice management: an approach for an engineering design organization. Int. J. Process Management and Benchmarking, 2 (2), 138–151.

Hamza, S.E.A. (2007b). The role of quality professionals in organizational

knowledge management: an extension to SOFCON experience. Proceedings of the

Hansen, M.T., Nohria, N. and Tierney, T. (1999). What’s your strategy for managing knowledge? Harvard Business Review, 77 (2), 106–116.

ILO (2007). Global Employment Trends Brief. International Labor Office, Geneva, www.ilo.org/trends.

Leitch, J.M. and Rosen, P.W. (2001). Knowledge Management, CKO, and CKM: The

Keys to Competitive Advantage. The

Kim, S., Suh, E. and Hwang, H. (2003). Building the knowledge map: an industrial case study. Journal of Knowledge Management, 7 (2), 34-45.

Koh, H., Ha, S., Kim, T. and Lee, S.H. (2005). A method of accumulation and adaptation of design knowledge. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology, 26 (9-10), 943-949.

Miles, R.E. and Snow, C.C. (1978). Organizational strategy, structure, and

process.

Millman, A. (1993). The Emerging Concept of Relationship Marketing. Ninth

Industrial Marketing and Purchasing Conference,

Murray, P. (2002). Knowledge Management as a Sustained Competitive Advantage. Ivey Business Journal, March/April 2002, 77-76.

Nadeau, A., Salokhe, G.,

Nonaka,

Nonaka,

Obaide, A. and Alshawi, M. (2007). A Holistic Model for Knowledge Management Implementation. International Journal of Excellence in e-Solutions for Management, 1 (1), 1-22.

Oliver, C. (1997). Sustainable competitive advantage: combining institutional and resource-based views. Strategic Management Journal, 18 (9), 697-713.

Polanyi, M. (1983). The Tacit Dimension.

Rebernik, M. and Sirec, K. (2007). Fostering innovation by unlearning tacit knowledge. Kybernetes, 36 (3/4), 406-419.

Teece, D.J. (2000). Strategies for managing knowledge assets: the role of firm

structure and industrial context.

The Economist (2005). Know how: Managing knowledge for competitive advantage. The Economist Intelligence Unit, sponsored by Tata Consultancy Services, June 2005, 1-19.

Contact the Author:

Salah

Eldin Adam Hamza, Quality Manager, SOFCON Consulting Engineering Co., Al Khobar

31952, Saudi Arabia; Tel. 00966554500484; Fax. 0096638879524; Email: salaheah@hotmail.com