Journal of Knowledge Management Practice, Vol.

10, No. 4, December 2009

Knowledge Management In e-Government

Priti Jain, University

of Botswana , Gaborone

ABSTRACT:

Today, knowledge is increasingly recognized as an important, strategic resource by all types of organizations and institutions, whether private or public, service oriented or production oriented. Regardless of the importance ostensibly attached to it, public sector organizations have often been less inclined to fully explore the benefits of knowledge management than the private sector. This paper will focus on knowledge management in the public sector. Common challenges and concerns that affect public sectors worldwide are identified as: driving efficiencies across all public services; improving accountability; making informed decisions; enhancing partnerships with stakeholders; capturing the knowledge of an ageing workforce, and; improving overall performance. To deal with these challenges public sectors often introduce several reforms including knowledge management and most recently, e-government. The success of e-government depends on knowledge management. Knowledge management provides the overall strategy and techniques to manage e-government content eloquently in order to make knowledge more usable and accessible and to keep it updated. This paper will posit how knowledge management can be put into practice as a reform instrument and an integral part of e-government to address some of the above challenges and lead the public sector to increased effectiveness, efficiency and productivity.

Keywords: Knowledge

management, Public sector, e-Government, Information technology

1. Introduction

Public sectors around the world are striving to be ever more efficient and effective in order to deal with the constantly evolving needs of their citizens. This is so, because, “increasingly, customers of the public sector are demanding higher service quality, particularly in the area of e-government. Services, particularly e-services, are expected to be available all the time with immediate response, simplified and with one-stop processing” (Luen & Al-Hawamdeh, 2001: 311). The common problems are: loss of knowledge with the retirement of older employees (Cong & Pandya, 2003, Knudsen, 2005, McNabb, 2007); problems of retaining vibrant staff (Knudsen, 2005); reduced budgets (Kandadi & Acheampong, 2008, Luen & Al-Hawamdeh, 2001, Knudsen, 2005); bureaucracy (Kandadi & Acheampong, 2008), and political exigencies (Kandadi & Acheampong, 2008). All these problems challenge public sectors in terms of driving efficiencies and effectiveness of their services. Demands and expectations encompass transparency, improved accountability; informed decision and policy making; enhanced partnerships with stakeholders (Riege & Lindsay, 2006); connecting silos in various public sector divisions and capturing the knowledge of an ageing workforce (Robertson, 2004); higher returns on taxpayers’ money (Riege & Lindsay, 2006, Mackay & Plimley, 2007); global acceleration of the push to implant e-government (Asoh, Belardo & Neilson, 2002, McNabb, 2007, Yuen, 2007) and; developing new/consolidating existing to improve overall performance.

To solve these common problems public sectors around the world have introduced several reforms with e-government being one of the most recent. Increasingly, e-governments are becoming part of public sector, but not taking off quickly. The transformation phase from manual to e-government therefore clearly has problems. Often, e-government websites look haphazard because of poor organization of knowledge. E-contents are not organized meaningfully to make them usable and easily accessible. E-governments are simply taken as transformation from manual to digital. Either all government information is not available through the e-government portals or e-portals do not allow people to interact with available information. As all the above issues concern organization and access to knowledge, the management of knowledge becomes critical to the success of e-government initiatives.

A lot has been written in both developed and developing countries on e-government. Various success factors have been identified for e-governments such as, administrative change, organizational change, resource allocation, values and cultural changes, legal and regulatory changes, strong leadership, good IT infrastructure, human resources, managerial skills, external/financial support etc. (Shin et al 2008). Knowledge management has received less attention than other aspects of e-government. This paper focuses on the application of knowledge management to make e-government initiatives successful and effective.

2. Concept Of Knowledge

Management

Traditionally, knowledge is depicted hierarchically, as an ascending pyramid evolving through four stages. Data, the raw facts or observations (O'Brien 1993), form the base and are processed to the information stage, when the data are assembled in a comprehensible form capable of communication (Harrod's librarians' glossary & reference Book, 2000). The third stage is knowledge, which is defined as "information that is relevant, actionable, and based at least partially on experience" (Leonard & Sensiper, 1998). In this stage the user has accessed the needed information, which will create knowledge. The last stage is wisdom, the "ability to perceive or determine what is good, true or sound" (Collier's Dictionary 1986:1142). Wisdom is the pinnacle of the pyramid and refers to the application of knowledge. This paper explores a new perspective: a horizontal approach, where knowledge also expands or multiplies sideways. This involves the creation, transfer and sharing of knowledge. For example, knowledge practices in one department spread out to another department and gradually thereafter to the whole organization. When its scope expands, knowledge becomes more complex and the need to manage it.

Basically, knowledge can be categorized as explicit and tacit knowledge. Explicit knowledge is documented, articulated into formal language, formally expressible and easily communicable; whereas, tacit is hard to put into words. It is expressed through action used by employees to perform their work and achieved during socialization, face-to-face meetings, teleconferencing and electronic discussions forms.

In a specifically organizational perspective types of knowledge are further defined and depend on the nature and purpose of the organization. The most common types can be tacit, explicit, cultural, innovative and customer knowledge. At government level, types of knowledge depend on the functions of the government. Government is the highest knowledge consumer and knowledge producer. Commons sources of knowledge in government are: visions and national strategic plans, government documents, laws, rules and regulations, notifications, archives, and directives among others. Thus, there is a wide array of knowledge content in the government that needs to be managed. Some people still have a misconception that knowledge management is another name of Information Technology (IT). IT remains an essential knowledge management facilitator but it is not just about information technology. In addition to information technology several other factors play an important part. There are culture, story-telling, people, processes, communities and organizational learning. Knowledge management compliments other management and learning initiatives and adds value to them through an action-based goal-oriented and holistic approach.

2.1. Definition of Knowledge

Management

Knowledge Management (KM) has been defined in differently by various authors and practitioners. For the purpose of this paper Misra’s (2007) approach is adopted, who defines knowledge management for government (KM4G) as “leveraging knowledge for improving internal processes, for formulation of sound government policies and programmes and for efficient public service delivery for increased productivity”. This definition fits best in the context of this paper, because it is for the government and it is an inclusive definition. By managing knowledge the public sector can leverage efficiencies across all public services through accessing the right information for making informed decisions and eliminating duplication of effort in its various branches. By capturing tacit knowledge of an ageing workforce and by availing easy access to all relevant information it can enhance partnerships with all the stakeholders and by doing so improve the overall performance of the public sector.

3. Concept And Definition Of

e-Government

e-Government means different things to different people with interpretations ranging from a government web-site, to digital government, internet worked government and so on. Generally speaking, e-government is associated with the use of the most recent information and communication technologies, where all government information is available in digital form.

Misra (2007) defines knowledge management (KM) for e-government as “management of knowledge for and by e-government for increased productivity. KM4Eg is a management tool for government decision makers and its programme implementers”.

According to the Institute for development Policy and Management (2008), “e-government is the use of information and communication technologies (ICTs) to improve the activities of public sector organizations” and it covers: “Improving government processes: by bringing e-administration, making strategic connections in government, connecting citizens: through e-Citizens and eServices and providing them improved services time and cost-effectively, building external interactions through e-Society having good relationship between public agencies and other institutions”.

Heeks (2008) further explains that e-government covers the following three main areas:

Ø Improving government process / e-Administration by making processes time and cost effective, managing process performance, making strategic connections in government, and creating empowerment;

Ø Connecting citizens (e-Citizens and e-Services) by providing citizens with public sector activities details, increasing citizen input into government decisions and actions and improving public services;

Ø Building external interactions by creating an e-Society, that involves improved relationships between public agencies and other public and private companies, interaction between government and business (Heeks, 2008). E-government requires internet-based technologies to provide facilitated access to government information and services, and citizens and enterprises engagement through e-government portals as a collective vision of all government activities.

Thus, e-government can be used to refer to a government that uses IT and e-commerce to provide access to government information and delivery of public services to citizens, and all other business partners and stakeholders including private sectors. E-government is citizen-centric.

4. Importance Of Knowledge

Management In e-Government

Knowledge management provides the overall strategy to manage the e-content of e-government by providing knowledge organization tools and techniques, monitoring up datedness of knowledge contents and availing all necessary information to citizens. Zhou & Gao (2007) have identified three benefits of knowledge management in e-government as being conducive to enhance governments’ competence, to raise governments’ service quality, and, to promote healthy development of e-government. Knowledge needs to be managed time and cost effectively in order to connect citizens to citizens and citizens to government and vice versa to make participative government policies and decisions. That brings government transparency and citizen empowerment and buys in of government projects and policies and consequently results in a more citizen centric government. So, the success of e-government depends heavily on knowledge management. “Knowledge management for e-government is no longer a choice but an imperative if economies have to survive in the unfolding era of privatization, liberalization and globalization” (Misra, 2007). Thus e-government is not merely a transformation from manual to digital; it is a collective vision of all government activities, vision and mission. Since e-government is largely knowledge intensive, it requires knowledge management applications and techniques to represent government fully and appropriately. This raises several issues of concern in e-government.

5. Major Issues Of Concerns

In e-Government

There are a number of major issues of concern faced in e-government, identified below:

Ø E-government content is haphazard: Often contents are not meaningfully organized for an easy access of information.

Ø Information is not updated regularly, which hinders informed decision making in all sectors of government and non-government. For example, in the tourism industry, information is of great importance for both public and the private sectors to make informed policies. Out of date information and dead links frustrate users and sometimes they may be unaware that the information concerned is redundant.

Ø All necessary information is not available, that leaves an e-portal incomplete.

Ø Most e-government sites do not allow for citizen-government interaction. This hampers citizen empowerment and government transparency; while knowledge management is a dynamic and interactive strategic management tool.

Ø Use of obsolete information technology: often the latest information technologies are not used or embraced quickly enough to keep the pace with the global society, and this influences the e-government initiatives negatively.

Ø Government portals are often designed by ‘non professionals’, who are not trained in knowledge application tools and techniques. They do not know how to adequately create, capture, store, share and update the site information.

Ø

Knowledge is presented in a

standard format, which may not be suitable for all citizens and stakeholders.

To solve this problem, some e-governments have started multi-channel delivery

of services offline and online (Misra, 2008).

Ø Data mining and knowledge management implications: Data mining is another tool to obtain information and aid in making informed decisions. In e-government the focus of data mining is predominantly on the management of interactions between the government and citizens or business, whereas, using data mining a good deal of knowledge can be extracted from several government transactional data and enhance decision making capabilities.

Ø Faulty approach to e-government: the current e-government practice in developing economies is project-specific (Misra, 2007). This approach thwarts e-government initiatives. Since e-government instigation aims at improved government services, it should not be seen as a project that can be ‘done and dusted’ and forgotten. It should be seen as a government-wide ongoing approach, where knowledge needs to be reviewed and updated to avail the most recent information to citizens and other stakeholders.

Ø There is a lack of strong leadership to understand, motivate, involve, influence and support e-government initiatives.

Ø

Budgetary

constraints obstruct the affordability of basic infrastructure for

e-government.

Ø

There

is a lack of good policies and legislation to provide a roadmap and action plan

to manage knowledge on government e-portals; and,

Ø A lack of understating of ethical behavior in e-government is another issue of concern.

6. Knowledge Management

Applications For e-Government

Most of the above mentioned e-government issues are revolving against content management; knowledge management can offer a number of applications and techniques to e-government:

6.1. Community Of Practice

(Cop) To Capture And Share Knowledge

“Communities of practice are groups of people who share a concern, a set of problems, or a passion about a topic, and who deepen their knowledge and expertise in this area by interacting on an ongoing basis” (Jashapara, 2004:203). CoPs produce mutual practices as members engage in a collective process of learning. CoPs can be online, digital and face-to-face. They can be informal and formal, within the government, outside the government with private sector, citizens’ rural communities, and non-government organizations. Tacit knowledge in government can often be more important than explicit, however, capturing tacit knowledge remains a major challenge. No technology or database can capture all knowledge. CoPs have proved the most powerful tools for learning and sharing knowledge for intellectual interaction and experience. They can be used to capture retired and older government employees’ knowledge; connect silos in various public sector divisions and to market government’s new initiatives.

6.2. Knowledge Organization

Tools

There are many knowledge organization tools borrowed from library and information science such as thesauri, classification schemes, subject heading schemes, taxonomies and ontologies, knowledge maps, intranet, discussion list archives, e-mail archives, websites. All these knowledge organization tools can be very useful for e-government content organization. For example, the Chinese government has adapted ontology-related technology to the knowledge management problem of e-government digital archives (Jiang & Dong, 2008).

6.3. Knowledge Maintenance

Tools

Knowledge management is meaningful only when accurate, relevant, necessary and up-to-date information is available to the right people at the right time and in the right format in a cost effective way. To achieve this, knowledge management emphasizes the importance of knowledge maintenance. Here we have to look at both knowledge quality and quantity. Maintenance of knowledge involves reviewing, refining, preserving and updating both implicit and explicit knowledge. Various knowledge maintenance systems are available to assist the process of knowledge maintenance.

6.4. Social Network Analysis

(SNA)

Similar to knowledge mapping SNA is a tool to analyze how nodes and users are interlinked. It maps and measures the relationships and flows between people, groups, organizations, computers, and websites or other information and knowledge processing entities and presents a visual and mathematical analysis. SNA identifies knowledge brokers and connectivity gaps. This is an essential activity for knowledge management in e-government, to measure and ensure the smooth flow of knowledge.

6.5. Knowledge Harvesting

Knowledge harvesting is a new dimension in the established field of

knowledge management system that is used to elicit a contributor’s tacit

knowledge. It can be a very useful technique in capturing government

employees’ tacit knowledge and making it accessible to others.

Information technology has provided numerous systems for knowledge harvesting,

such as, Electronic Document and Records Management (EDRM) and

6.6. Knowledge

Management Portals

Knowledge management portals are

another knowledge management tools “to extract analyze and categorize

both structured and unstructured information, and reveals the relationship

between content, people, topics and user activities in the organization. They

can provide users with many interactive facilities such as e-mail, chat rooms,

personalized news, search engines, RSS feedbacks, and external links. In

7. Basic Framework For

Knowledge Management In e-government

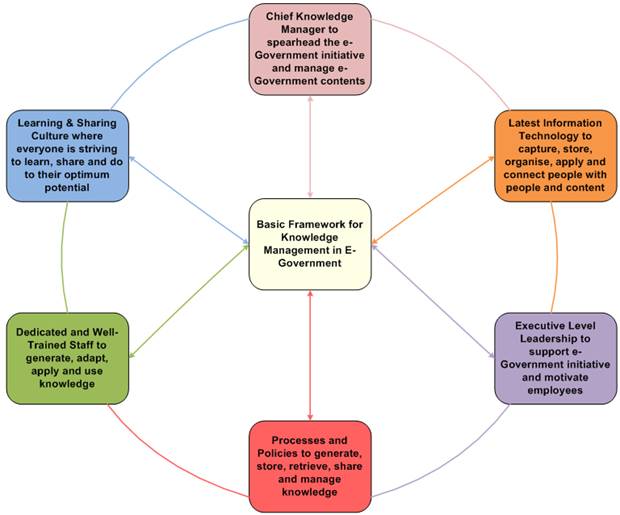

Figure 1: Basic Framework For

Knowledge Management In e-government

To manage knowledge in e-government the above framework needs the following six major constituents:

i. Chief Knowledge Manager (CKM):

There should be a well-trained chief knowledge manager, who sets up a dedicated e-government office to steer and co-ordinate all e-government initiatives. Responsibilities would cover knowledge mapping, knowledge auditing, deciding which services to be provided electronically, creating awareness of knowledge management and e-government’s joint benefits, facilitating the ongoing process of knowledge sharing, knowledge renewal and evaluation, updating knowledge content regularly and setting up an environment to aid flow and grow of knowledge. The incumbent should thus be a pioneer in exploring new knowledge frontiers, able to identify best practices, capture lessons learned and interpret them in context. CKM should be a visionary and strategic thinker always aiming to obtain and sustain a competitive edge and who can persuade people for a change of mind-set.

ii. Latest Information Technologies:

To practice knowledge management most effectively, the latest information technologies should be exploited. These would include Wimax, the latest wireless broadband technology, and content management systems to capture, create, store, transfer, share, and display, evaluate, maintain and update knowledge. Currently available relevant systems include Customer Relationship Management (CRM) to manage interactions between government and its customers, and Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) to maintain and update knowledge and iSite Web Content Management System and special Content Management Systems (CMSs). In planning all this, Government has to first establish its priorities as for the example the Singapore Government did when it announced its IT priorities for 2009.

iii. Executive Level Leadership to support e-government:

Knowledge management needs full support from government executive management, who can stimulate financing and win the support from other employees, executive decision makers and all other stakeholders. Since e-government is citizen-centric, government should “recognize the diverse roles that citizens can play as partners, taxpayers, constituents, employers, employees, students, investors and lobbyists” (Ndou, 2004:16). All of this calls for a decisive leadership from the top government management.

iv. Processes and Policies:

Processes and policies are important to provide a roadmap on how government knowledge can be better managed. The knowledge management strategy is the foremost important document in initiating knowledge management practice. It is like an integrated framework to maximize organizational capabilities and leverage existing knowledge. It should be based on the real needs of the government, gathered through a knowledge mapping and knowledge auditing exercise, and should be an all encompassing strategic planning document, aligned with government mission and vision. It must include a knowledge management vision, mission, and background, challenges, implications and entire action plan.

v. Dedicated and Well-Trained Staff:

Properly trained and committed staffs are critical in making knowledge management in e-government a success. True, "IT has its intended usage in the context of KM; human motive and willingness are the underlying factors that dictate the actual IT usage" (Yahya & Goh 2002:460). Dedicates staff will always remain the main driver behind knowledge management.

vi. Learning and Sharing Culture:

There is a need for a conducive environment where people do not feel forced to share knowledge but rather have a constant desire to learn together, so that they complement each other. This is the biggest challenge in knowledge management and yet the most important factor.

8. Content Management For An

e-government

The author suggests the following 8-Points for an e-government content

management:

Ø

Knowledge

mapping and knowledge auditing in order to identify and address the real

knowledge needs and problems of the public sector;

Ø Formulation of a knowledge management strategy in the e-government environment based on the knowledge mapping and knowledge auditing findings;

Ø

Raise

awareness of knowledge management and e-government benefits at all levels of

government to win the support from everyone;

Ø

Identification,

creation and capture of new knowledge; to

publish all important information on the e-portal;

Ø

Storage

and organization of all important knowledge for easy retrieval and increased

effectiveness and efficiency;

Ø

Use

and re-use of knowledge for maximum efficiency;

Ø

Transfer

and sharing of knowledge through social and electronic networks; and,

Ø

Maintenance

and Assessment of Knowledge; by reviewing, refining, preserving and updating

both implicit and explicit knowledge in order to maintain the quality,

relevance, accuracy, comprehensiveness and timeliness of information.

9. Conclusion

Based on the foregoing debate it is concluded that knowledge management must be considered as an integral part of e-government and knowledge management professionals should be involved in designing e-government portals. Success depends on how each government, ministry and department can exploit these two reformative, complementary instruments using them as strategic competitive tools in the modern global e-society.

10. Recommendations

To make a successful e-government it is further recommended that:

Ø E-government should not be limited to a project level, but should be seen a comprehensive government wide ongoing process;

Ø There is a need of change management ; individual change of mind-set and governmental change to keep pace with the global changes to gain and sustain a competitive edge;

Ø There should be strong collaboration at local, regional and national levels and between public and private sector organizations;

Ø Knowledge management portals should be based on citizen empowerment and interaction and they should provide multi-channels delivery of public services to cater for all levels of citizens and stakeholders.

Ø There is a need of decision support systems for designing new services tailored to citizen needs and suitable for a complex E-government scenario (Meo,2008).

11. References

Asoh, D., Belardo, S., Neilson, R. (2002), Knowledge Management: Issues,

Challenges and Opportunities for Governments in the New Economy. Proceedings of

the 35th

Collier's Dictionary (1986). Edited by W.D. Halsey, Macmillan Publishing,

Cong, X., Pandya, K. V. (2003), Issues of Knowledge Management in the Public Sector. Accessed 4 May 2009: http://www.ejkm.com/volume-1/volume1-issue-2/issue-2-art-3-cong-pandya.pdf.

Harrod's librarians' glossary &

reference Book (2000), Prytherch, R. (comp.), Gower,

Heeks, R. (2008), What is E-Government? Accessed 14 March 2009: http://www.egov4dev.org/success/definitions.shtml.

Institute for development Policy and Management. (2008), What is e-Government? Accessed 23 March, 2009: http://www.egov4dev.org/success/definitions.shtml#definition.

Jashapara, A. (2004), Knowledge Management: An Integrated

Jiang, Y., Dong, H. (2008), Towards Ontology-Based Chinese E-Government

Digital Archives Knowledge Management, Springer-Berlin

Kandadi, K. R., Acheampong, E.A. (2008), Assessing the knowledge management capability of the Ghanaian public sector through the “BCPI Matrix”: A case study of the value added tax (VAT) service. Accessed 14 March 2009: http://works.bepress.com/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1000&context=edwin_acheampong.

Knudsen, J.S. (2005). Public Sector Knowledge Management in

Leonard, D., Sensiper, S. (1998), The role of tacit knowledge in group innovation, California Management Review, 40(3), 112-32.

Luen, T.W., Al-Hawamdeh, S. (2001), Journal of Information Science, 27(5), 311-318.

Mackay, G and Plimley, N. (2007), Rethinking public sector knowledge management. Accessed 15 March 2009: http://uk.fujitsu.com/POV/localData/pdf/know-problem.pdf.

McNabb, David E. (2007), Knowledge Management in the Public Sector: A Blueprint for Innovation in Government; Accessed 14 March 2009: http://books.google.com/books?id=WSc102GMZ9cC&dq=knowledge+management+in+public+sector&source=gbs_summary_s&cad=0.

Meo,P.D. (2008), A decision support system for designing new services tailored to citizen profiles in a complex and distributed e-government scenario, Data & Knowledge Engineering, 67(1), 161-184.

Misra, D.C. (2007), Ten Guiding

Principles for Knowledge Management in E-government in Developing Countries;

Accessed 19 April 2009: http://unpan1.un.org/intradoc/groups/public/documents/UNPAN/UNPAN025338.pdf.

Misra, D.C. (2008), Ten Guiding

Principles for E-government, Accessed May 2009:

http://egov-india.blogspot.com/2008/09/ten-guiding-principles-for-e-government.html.

Ndou, V. (2004), E-Government for Developing Countries: Opportunities and Challenges, The Electronic Journal on Information Systems in Developing Countries, (18), 1-24.

O'Brien A.J. (1993), Management Information Systems: A Managerial End User Perspective, Irwin, Burr Ridge, 2nd ed.

Riege, A., Lindsay, N. (2006), Knowledge Management in the public sector: stakeholder partnerships in the public policy development, Journal of Knowledge Management. 10(3), 24-39.

Robertson, J. (2004), Developing a

knowledge management strategy, Accessed 14 March 2009: http://www.steptwo.com.au/papers/kmc_kmstrategy/.

Shin, S., Song, H., Kang, M. (2008), Implementing E-Government in Developing Countries: Its Unique and Common Success Factors, Accessed 19 April 2009: http://www.allacademic.com//meta/p_mla_apa_research_citation/2/8/0/1/7/pages280176/p280176-1.php.

Yahya, S., Goh, W-K, G. (2002), Managing human resources toward achieving knowledge management, Journal of Knowledge Management, 6(5), 457- 468.

Yuen, Y.H. (2007), 7th Global Forum on Reinventing Government: Building Trust in Government (Workshop on Managing Knowledge to Build Trust in Government) Accessed 14 March 2009: http://unpan1.un.org/intradoc/groups/public/documents/unpan/unpan026041.pdf.

Zhou, Z., Gao, F. (2007), E-government and Knowledge Management. IJCSNS International Journal of Computer Science and Network Security, 7(6), 285-289.

About the Author:

Dr. Priti Jain is currently,

lecturer in the Department of Library and Information Studies at the

Dr. Priti Jain, Lecturer, Dept. of Library & Information Studies,