The

Psychological Contract, Knowledge Management & Organisational Capacity

Deborah Blackman, Dianne Phillips, University of Canberra

ABSTRACT:

This paper considers the relationships between the psychological contract and the propensity to create, share and utilise organisational knowledge, thereby developing potential organisational capacity. It is widely accepted that organisational capacity will be affected by the way that knowledge is utilised within an organisation. It is argued that the way that individuals feel about their organisation must, inevitably, affect their willingness to engage with activities that lead to effective knowledge management and, consequently, the capacity of an organisation to improve and innovate will be determined by the psychological contract present within the organisation. Three case studies undertaken in the hospitality education industry are used to identify four key themes which affect the effectiveness of organisational knowledge management and are affected by the psychological contract: functionality, safety, opportunity and relationships. The final part of the paper begins to identify strategies that will support knowledge creation and absorption and, consequently, increase of organisational capacity within firms.

Keywords: Knowledge management, Psychological contract, Organisational capacity, Knowledge economy

1. Introduction

In recent years, organisations have come to realise that what they

‘know’ is crucial to their competitiveness (De Geus, 1997; Teece et

al, 1997; Stewart, 1997 in Little

et al, 2002), as this is one of the ways

in which organisational capacity is developed. Hinings and

This current growth of interest about knowledge has led to many publications considering the concept and the issues surrounding it. Pérez-Bustamante (1999), discusses knowledge management in agile, innovative organisations, describing knowledge as the foundation of intellectual capital; this is in itself a major consideration in innovative environments and relates the importance of an organisation's internal knowledge capacity as a primary source of innovation. Pitt and Clarke (1999) note the role of knowledge in innovation, stating that an organisation must purposefully apply its skills and knowledge to achieve strategic innovation. Those in control of organisations, who manage and organise capacity in today’s knowledge economy, are realising the value of the knowledge they already contain for providing solutions to improve organisational capacity. Knowledge management is being increasingly discussed as one of the desired processes for developing organisational capacity (Swan et al, 1999 and 2002); the argument is made that by managing the learning and knowledge creation processes carefully and developing an innovative culture, greater organisational capacity can be achieved (Lam, 2003; Jones, 2001; Johannesse et al, 1999).

This paper considers the

relationships between the psychological contract and the propensity to create,

share and utilise organisational knowledge, thereby developing potential

organisational capacity. Initially, the

paper reviews the literature, which links together knowledge, the psychological

contract and their relationship to organisational capacity. Three case studies

undertaken in the hospitality education industry are then used to clarify the

relationship between the psychological contract and knowledge management. The

final part of the paper identifies how this affects knowledge creation and

absorption and, consequently, the potential organisational capacity within

firms.

2. Knowledge, The Psychological Contract And Organisational

Capacity

Broadly, a psychological contract

emerges “when one party believes

that a promise of future returns has been made” (Bellou, 2007, p. 69) and it refers to an individual’s

understanding of what those promises and potential reciprocal exchange

agreements are (Rousseau, 1995; Bellou, 2007; Coyle-Shapiro and Kessler, 2000).

In the case of this paper the reciprocal exchanges will be between the employee

and the employer. There is a range of perspectives on what exactly the contract

is, as well as which parties should be included: Cullinane and Dundon argue

that “Some authors emphasize the

significance of implicit obligations of one or both parties; others stress a

need to understand people’s expectations from employment; while another

school of thought suggests that reciprocal mutuality is a core

determinant” (2006, p. 115). However, in all cases, an employer or an

employee will develop a mental model or schema of the employment relationship,

which will affect the way that they frame events within the workplace and,

therefore, react to them (Rousseau, 2001; Bellou, 2007, Blackman and Phillips,

2007). In this paper we argue that, given the way that they will impact upon

the propensity and potential to share and create knowledge, psychological

contracts will affect the way that new knowledge development occurs.

There is already an established link

between the psychological contract and the success of change initiatives (Pate

et al, 2000; Maguire, 2002) because outcomes are affected by individual

emotions. A view of knowledge as a socially created, evolving phenomenon

affected by relationships between individuals and their organisations, led

Blackman and Davison (2010) to posit a relationship between the psychological

contract and knowledge management, arguing that knowledge creation and sharing

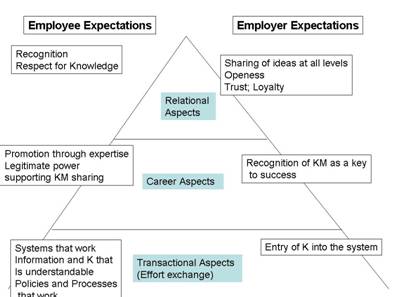

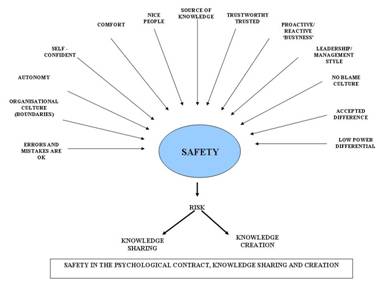

will be affected by the emotions felt by those involved (see figure 1). There

are three levels identified as needing to be considered: the transactional

level, the career level and the relational level.

Transactional contracts are usually

short-term and performance related, involving set monetary exchanges (Rousseau,

1989; D’Annunzio-Green and Francis, 2005). A good example of such a

contract would be hiring a first employee to do administration in an office;

commitment and development of skills is negligible and a specific wage rate and

period of employment is agreed upon which can be amended if required later.

There can be transactional elements within any psychological contract – aspects

of a job which are seen to be straightforward with the assumptions about what

is needed and expected being clear. For example, in figure 1, issues to do with

a computer system would be transactional – they are expected to be

straightforward and have little to do with long term trust.

Figure 1: The Psychological Contract In Terms Needed

For Effective Knowledge Management

(Source: Blackman And Davison,

2010)

The second level, the career aspect is mediated by what employees believe is appropriate for their mid to long term future with a company (Maguire, 2002). This is likely to have an impact upon employment, as there may not be development of a long-term relationship unless employees can see that they are going to be (a) likely to have the potential for job security and (b) are going to be treated both with respect and as an important part of the organisation. In general, recognition of the need for the individual’s career aspects to be considered is a starting point for developing a more relational association with employees – if there is no development of role possible within an existing firm, there may need to be a commitment to develop skills to enable an employee to be mobile. This may seem to be counter intuitive and to encourage employees to leave, but if they are feeling supported they may stay on and be more capable of new knowledge creation for longer.

Relational contracts are based on an emotional involvement as well as merely financial reward (Rousseau, 1989; D’Annunzio-Green and Francis, 2005). They tend to be far more long-term and involve significant loyalty and discretionary behaviour aspects by both the employer and employee, leading to an identification with the firm. Blackman and Hindle (2008) demonstrated that often employers expect their employees to be relationally committed to a venture, despite their not really having an interest or history in the firm. Such expectations can lead to unrealistic aspirations of new knowledge creation and innovation which will not be achieved; consequently hoped for increases in capacity may not emerge.

Organisational capacity is an organisation’s ability to become more competent in its acquisition and use of resources of all kinds in order to better deliver the products or services that are its primary purpose (Honandle, 1981). To achieve organisational capacity, organisations need to consider the interrelations of any number of elements in order to produce new strategies, arrangements and capability configurations (Miller et al, 2002 in de Wit and Meyer, 2005) which will enable organisational development and growth. These elements will include not only institutional and human infrastructure, but also any other components which affect organisational learning which, some would argue, are the underpinning processes that enable capacity growth (Lam, 2003; Jones, 2001; Senge, 1990, Senge et al 1999). If learning is to be developed and supported then relational aspects such as common values and trust, as well as processes and systems designed to engender feelings of safety, security and respect will be needed in order to enable the development of new ideas and innovations (Edmondson, 1999; Senge et al, 1999). The key is that the reason for supporting learning is to develop new knowledge (Blackman and Henderson, 2005), which will enable new capabilities to emerge from the increased capacity (Miller et al, 2002 in de Wit and Meyer, 2005).

It is argued that capacity building is more than merely training but includes equipping individuals with the knowledge which enables them to perform effectively. This indicates that the augmentation of knowledge will be vital for the success of the growth of organisational capacity but, as it is about the management of people, it may have specific issues in the development and sharing of knowledge in new and/or small firms, particularly where knowledge is seen as being created via the interactions between individuals. Nonaka and Konno (1998), for example, describe socially based knowledge generation and note that participation in a social situation defines what knowledge is and what information is. What can be seen here is that, not only will the creation of knowledge be affected by the psychological contract and the way that people feel, but so will their likelihood to then share these ideas and innovative practices with their employers to fulfil organisational aspirations that reach capacity. Consequently, it seems likely that the state of the psychological contract will have a direct effect upon the potential success of organisations to reach their capacity.

3. Methodology

The paper is based upon empirical data gathered from three case studies in the hospitality industry which clarifies the relationship between the psychological contract, knowledge management and organisational capacity. There is a lack of current data about these areas and so a qualitative approach was selected, in order to develop an understanding of the phenomena (Leedy and Ormrod, 2005; Creswell, 1994) and their implications.

The three cases were chosen as, although the organisations were similar in their size and product, they had very different psychological contracts; they ranged from very good, through average to extremely negative in the third. The contracts were established through metaphor analysis whereby respondents were asked to give metaphors that described their feelings towards their organisations at the time of the interview. These were then compared and an overall picture of the state of the psychological contract for each organisation was established (Schmitt, 2005).

The qualitative studies were undertaken using in-depth semi-structured interviews and focus groups from a variety of stakeholders within and around the hospitality industry. 14 focus groups were held that involved 45 people in total (this represents 40 % of the total staff involved in the three case study locations). 15 interviews, which lasted about 30 to 45 minutes each, were undertaken which reflected the same population as the focus groups. Similar questions were asked in each data collection method and a comparison was made early on before all the data had been collected, in order to establish whether a similar pattern of data was emerging in each mode of collection. As this proved to be the case it was not considered necessary to interview all the respondents individually but to continue to develop focus group responses. The data was entered into NVIVO and coded, enabling an analysis using axial and thematic coding to be used (Pandit, 1996). This coding allowed themes to emerge which permitted a range of issues to be explored and the development of a model that linked knowledge creation potential, the psychological contract and organisational potential, capacity and performance.

4. Findings And Discussion

Four main themes emerged as the key influences upon knowledge sharing that were affected by the current state of the psychological contract: functionality of the knowledge sharing, opportunity for sharing, attitude towards the target sharer and the levels of perceived safety. Each of these will be explored in turn. It should be stressed that we are not claiming that these are the only aspects affecting knowledge sharing, but that these were elements demonstrated in the data as being affected by, or mediated in some aspects by, the psychological contract.

4.1. Functionality Of The

Knowledge Sharing

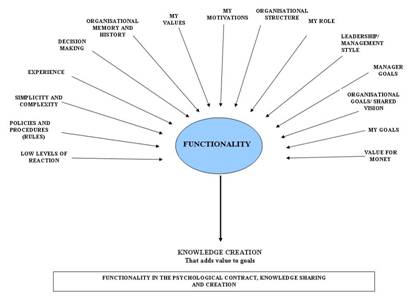

From the data, several aspects were seen to affect the sharing of knowledge in terms of the apparent functionality:

Ø Perceived

Usefulness: It should be no surprise, but a major factor

affecting the propensity to share was the perceived usefulness of the outcome

to the individual. What was slightly more surprising was that the perceived

usefulness of the knowledge to the other party was a major element of

consideration: “when we would like to share our knowledge to the manager, actually we

should think about whether the knowledge we have is enough for us to share with

our boss competently”.

Ø

Manager’s

Goals: There was an aspect

that whether the manager would want to hear something or not would predispose

the person to share, or not: “kind of depends on what they want to

hear”. There was an indication that anything deemed as irrelevant would

be ignored.

Ø

Policies and Procedures: There were practical reasons to share: “Not so

much my role, it’s just like a set of patterns for tasks, and over time I

guess I use them, but with experience you come to the solution of better ways

in which it might be done. And I find that’s usually prompting me to

share”. This is clearly affecting the transactional elements of the

psychological contract.

Ø

Role and Organisational Structure: There

was a view held by several people that competition engendered a reduction in sharing

as it would give power to others: “If there’s a competition I

wouldn’t share”; “If you have a boss who takes credit for

something you’ve done then you wouldn’t [share].” Structure

was also seen to be affecting knowledge creation and capacity in terms of silos

and competition between parts of the organisation “initially we were very

territorial, the established schools were nervous about us arriving”.

Ø Personal Values of Sharer: Affecting the propensity to

share is always whether there will be a long term benefit, which may not be

directly related to goals at work, but may reflect personal plans or aims:

“that comes back to benefit, you think the benefit of not sharing it,

will be that you might get promoted”. This can be seen to impact upon all

levels of the potential contracts, but will have the most impact where

employees have clear views as to where they wish to be in the future, thereby

affecting the career aspects.

Ø

Leadership/Management Style: This links to the idea of manager’s goals, in

terms of the more senior employees indicating what is of value to them and the

organisation. What will matter is that there is a clear message being developed

which will indicate to those within the organisation that all ideas are

welcomed: “For myself I find that leaders in an institution make a big

difference” was the opening part of an explanation that in a previous job

the individual had felt that there was no interest in what he did and so he did

not feel predisposed to get involved and share. Where there was direct

leadership involvement, he did feel a sense of urgency to develop and improve

things.

Overall, the issues reflecting utility can be summed up in Figure 2. The perceived usefulness in terms of personal gain, concern for others and organisational goals are all affected. All three levels of the psychological contract can be seen to have been influenced.

Figure 2: Elements Influencing The

Functionality Of Sharing Affected By The Psychological Contract

4.2.

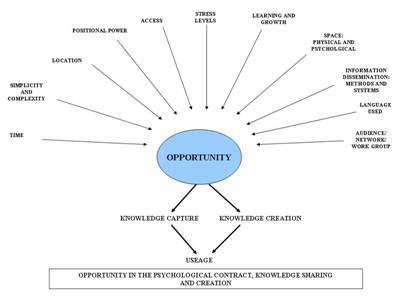

When asked what prevented knowledge

sharing a major factor was seen to be a lack of time, which led to greater

pressures and the need to reduce how much information and knowledge was being

moved around the system. It became clear that where employer and employee

expectations of how and when knowledge needed sharing were different, it was

less likely to occur and this is reflected in the following statement “the boss, the environment, learning

and challenge”.

Ø

Time: From both recently employed personnel and

more long term team members, the data discussed on time has been interpreted

as, it takes “time to understand the culture”. Timeliness of sharing and what appears as the

depth of knowledge about the organisation appear linked to sharing. This could

be thought of as organisational knowledge or power or understanding

organisational culture, or even “the right to comment”.

Ø

Location: Sharing a location did not seem to matter,

as a multitude of other relational factors such as trust, respect and

recognition affected sharing. Location of the management can be an issue which

influences sharing. If the management location is seen as an ivory tower and is

“located in one area” then limited sharing would occur. If

management is mobile and “are seen to come to you” this action

could enhance employees ability to share.

Ø

Lower stress: Transactional processes are important in

lowering stress factors; they seem to cover the day to day communication

sharing of information and knowledge. Transactional tools such as e-mail,

communal calendars, share drives, intranet, phone conversations, meetings

and even more formal tools such as

reports are, therefore, to the benefit of the organisation for all to share and

use. Such tools are used as routine, repetition and create habit and also

appear as a theme arising out of the data in relation to time. Just as routine and habit reduce cognitive

load, stress factors for sharing and time can be reduced. Actors working

patterns enhance sharing and knowledge and can “generate new ideas”. However, habits can also

create the opposite effect and inhibit the creative and critical thinking which

produces new knowledge and the need to share.

Ø

Space and Access: There is a realisation by participants that

space to reflect on “thinking about better ways of saying it… doing

it” (knowledge) is essential. As time is perceived as limited:

[we]…“Never…come back to it,

the knowledge issue. … Input …I see as an issue…you have to have a space to

reflect on things… in order to be able to improve…” Spaces

such as “reading time, study”, “listening time” or time

“when you are back home” working from home could be a space for

reflection and thinking time, in order to share more in the physical working

environment.

Figure 3: Elements Influencing The

4.3. Attitude Towards The

Target Sharer

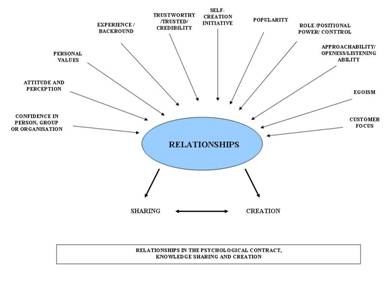

The way in which the target receiver (usually another individual) was perceived had a major impact upon the knowledge source’s willingness to develop new ideas and share them. Words frequently used were “trust”’, “respect”, “openness” and “equality”. Unsurprisingly, in cases where there were reports of “toxicity” or “evilness”, there was not only no propensity to share, but an actual resistance to it.

Ø Confidence in person, leader or organisation: Personal traits or cultural traits of the organisation that enhanced sharing were described in many forms. The principal recurring theme was personal values and traits which been seen as ‘good’, as can professional ethics and a strong positive organisational culture. A high level of confidence in leaders was also closely related to their level of knowledge. The data showed that this was vital in order for actors to share and understand information, to enable learning and pass on knowledge of a technical or expert nature and to provide confidence and thus sharing. Secondly, a “type of rapport [yes, yes] trust, respect… communication and understanding”, “makes me feel they have confidence in me” was noticeable. The theme of respect seems a reoccurring foundation for confidence in order to share. No matter the position of the person in the organisation, there was an element of expert knowledge that appeared to involve additional expectations and, as such, “Low levels of transparency by one manager” can significantly reduce the overall sharing in the organisation.

Ø Trustworthy/trusted: The attitude towards sharer, trust and to be

trusted can be discussed in terms of the time of service and an understanding

of the organisation. “When you stay a longer time the relationship is one

of trust”. Insight into the

organisations’ cultures emerged as a link to time and possible

competition, both within the corporate structure and between individual team

members.

Ø Role: Overall, the hierarchical role has been discussed within previous sections of the paper and, as previously noted, the expectation of role being linked with knowledge, power differentials and the expectation of high levels of sharing is a strong one. The organisational chart reflects such power aspects “we have our positions…but when it comes to sharing knowledge it doesn’t matter who you approach, they are all eager to help…everybody is on the same level…I feel more able to share information… as I feel we are on the same level and can contribute to the organisation”.

Ø Approachability: “If someone is more receptive… I am more likely to approach them and be comfortable with sharing” Pre-judgement is based on the previous experiences and perceptions of the actor; history acts as the guide, creating an image of the individual whereby if they are seen as accommodating and welcoming they are more likely to receive new ideas.

Figure 4: Elements Influencing

Attitudes Towards The Target Sharer And The Psychological Contract

4.4. Levels Of Perceived Safety

The fourth theme identified, which is linked to the issues of trust in the target sharer, was a strong aspect of perceived safety to be able to share. It was made clear that unless individuals felt safe, which was about mental certainty that there would only be positive outcomes, they would not feel inclined to develop ideas for the benefit of the community as a whole.

Ø Errors and Mistakes are Permissible: This was related to an atmosphere ‘no blame’ and ‘no fear’. This is clearly cultural and will emerge from the values and norms set by the leadership. It was made clear that leaders needed to actively demonstrate the safety they proposed, whether in terms of being seen to undertake development in order to encourage knowledge acquisition, or in actively supporting those who undertake initial sharing.

Ø Organisational Culture: Other

aspects of culture were also discussed: “There’s such a welcoming

aspect to the culture as well, and even when somebody new starts, well

…welcome into the family…..day one…not just sitting you down

and expecting you to do your job.. you know, every department joins in, wants

to get to know you, there is that relationship, that trust built in…and

the respect…”.

Another aspect of culture was whether sharing had been positively or

negatively responded to previously: “how my manager received things last

time [will affect it]”.

Ø Self-confidence: An

interesting issue that was raised was whether people felt able to share –

this was related to whether they thought they knew enough to be credible:

“their concerns were affecting their ability to learn... and therefore

the knowledge they get, their willingness to share their ideas, was clearly

limited with the school. They are concerned about the level of professionalism,

so the issues of comfort, certainty all of those things are affecting their

ability to work”. A related issue was that there needed to be confidence

that employers would want to hear what was being shared. This notion of

pre-judging ideas before sharing them came through strongly in several areas

within the data: “whether the manager likes to know the kind of knowledge

that I would like to tell him”.

Ø Comfort: It seems obvious, but it was raised on several

occasions that individuals would share if they felt comfortable with the people

they were going to share with: “If you’ve worked for a long time

… you’re obviously comfortable to share that knowledge with

[them]”: “after a very short time I was made to feel comfortable

around here, … I can knock on a door and go in”. Time issues were

discussed the other way as well: “I probably haven’t shared too

much up to date because I’m new”. This has implications for the

relational aspects of the psychological contract.

In

summary, three things were seen to emerge as a result of these issues: firstly,

individuals were more likely to take risks and share difficult and challenging

ideas if they felt safe; secondly, as a result of feeling safe they would be

more predisposed to share knowledge throughout their organisation and, thirdly,

the creation of new ideas and new innovations was more likely because they felt

encouraged to do so. These areas are particularly

pertinent to the transactional and relational aspects of the psychological

contract and the need to establish good relational aspects of contracts as

quickly as possible can be understood here.

Figure 5: Elements Influencing The

Levels Of Safety Affected By The Psychological Contract

By combining the different aspects above and considering which aspects of the psychological contract they are more likely to affect, we can model the propensity for knowledge sharing and the relational and transactional aspects of the psychological contract as shown in figure 6. The implications of this for the development of organisational capacity will be discussed next.

Figure 6: Propensity To Share And

Use Knowledge And The Psychological Contract.

5. Implications For

Organisational Capacity

From the research so far, there is strong empirical evidence to support the theoretical development of the link between the psychological contract and the creation, utilisation and storage of knowledge. We argue that this will, therefore, affect effective knowledge management and the potential for growth in the organisational capacity. As might be expected, a negative relational contract can be seen to be a most significant influence upon the capacity to share new knowledge – in case two where the most negative contract was to be found, the greatest number of reasons for limiting what would or would not be shared was demonstrated. As there were significant tensions between senior management and some of the other employees, they were clear that whilst they might recognise potential they would limit to whom and where that knowledge would be transferred. In the case with the most positive contract, such limitations were not raised. The element of risk was frequently raised as the decider in whether or not to share and this was determined by the state of the psychological contract.

However, it needs to be stressed that even where there is a positive contract there can, potentially, be barriers to capacity development. An unexpected, but significant finding was the idea of ‘pre-judging’ knowledge sharing. When asked whether there were factors that would affect the knowledge that they would share or their readiness to do so, many respondents argued that they would only share what they felt would be useful or relevant to the other party. Moreover, if they liked or respected an individual they would shelter them from too much new knowledge as they knew they were too busy. What is occurring is that the mental models held of what was needed for others to do their jobs were acting as unseen barriers to sharing; the stronger the mental model of the individual with the original knowledge, the more of a constraint it became. In terms of organisational capacity this is an important issue as, if new ideas and knowledge are not shared, it reduces the potential for greater capacity, stretched ideas and new capabilities. Senge (1990) identifies the need for tension if there is to be learning and an extension of ideas – if any differences are ignored or dismissed as unnecessary then such tensions will be avoided and new knowledge will not emerge. In such cases, ways to open the mental models will become a crucial management strategy.

6. Conclusions

This paper set out to explore the potential relationship between the psychological contract and knowledge management, with specific reference to how it might impact upon organisational capacity and practices. What has been demonstrated is that it will be important for organisations who wish to reach organisational capacity to consider the implications of a changing psychological contract, whether positive or negative. In terms of both transactional and relational aspects, the research indicates that the development of knowledge through a positive psychological contract will be more likely to lead to the successful development of organisational capacity but, as it is about the management of people, there may still be specific issues in the development and sharing of knowledge in firms, that need to be managed. The argument is that, by recognising the role of the psychological contracts in knowledge management, strategies can be chosen which will recognise how they can become barriers to effective knowledge transfer.

7. References

Bellou, V. (2007), Psychological contract assessment after a major organizational change: The case of mergers and acquisitions, Employee Relations, 29(1), 68-88.

Blackman, D., Davison, G. (2010), Psychological

Contracts and their Role in the Management of Knowledge in Organisations, International Journal of

Learning and Intellectual Capital; Forthcoming.

Blackman, D.,

Blackman, D., Hindle, K. (2008), Would using the Psychological Contract

increase Entrepreneurial Business Development potential? In Barrett, R. and

Mayson, S. (2008), A Handbook of Entrepreneurship and HRM, Edward Elgar,

Blackman, D., Phillips, D. (2007), Why the psychological contract is

important for knowledge management and innovation strategists,

Coyle-Shapiro, J., Kessler,

Creswell J.W. (1994), Research

design, qualitative and quantitative approaches, Routledge,

Cullinane, N., Dundon, T. (2006), The psychological contract: a critical review, International Journal of Management Reviews, 8(2), 113-129.

D’Annunzio-Green, N., Francis, H. (2005), Human Resource Development and the Psychological Contract: great expectations or false hopes? Human Resource Development International, 8(3), 327-344.

De Geus, A. (1997), The living company, Harvard Business Review, March/April, 75(2), 51-59.

De Wit, B. and Meyer, R. (2005), Strategy Synthesis: resolving strategy

paradoxes to create competitive advantage, Thomson Learning,

Edmondson, A. (1999), Psychological safety and learning behaviour in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, June, 44(2), 350-372.

Hinings, C.R.,

Honandle, B.W. (1981), A Capacity-Building Framework: A Search For Concept and Purpose, Public Administration Review, September/October, 575-580.

Johannessen, J.A., Olaisen, J., Olsen, B (1999), Managing and organizing capacity in the knowledge economy, European Journal of Capacity Management, 2 (3), 116-128.

Jones, M.L. (2001), Sustainable organizational capacity building: is organizational learning a key? International Journal of Human Resource Management, 12(1), 91-98.

Lam, A. (2003),

Organizational Learning in Mulitnationals: R and D Networks of Japanese and US

MNE’s in the

Leedy, P.D., Ormrod, J.E.

(2005), Practical Research: Planning

and Design, Merril Prentice Hall,

Little, S., Quintas, P., Ray, T. (2002), Managing Knowledge: an essential reader, Sage Publications.

Maguire, H. (2002), Psychological contracts: are they still relevant? Career Development International, 7(3), 167-180.

Nonaka,

Pandit, N.R. (1996), The Creation of Theory: A Recent Application of the Grounded Theory Method, The Qualitative Report, 2 (4), Accessed 1st August 2009: http://www.nova.edu/ssss/QR/QR2-4/pandit.html.

Pate, J., Martin, G.,

Pérez-Bustamante, G. (1999), Knowledge management in agile innovative organisations, Journal of Knowledge Management, 3(1), 6-17.

Pitt, M., Clarke, K. (1999), Competing on competence: a Knowledge Perspective on the management of strategic innovations, Technology Analysis and Strategic Management, 11(3), 301-317.

Rousseau, D.M. (1989), Psychological and implied contracts in organizations. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 2(2), 121-139.

Rousseau, D.M. (1995), Psychological Contracts in Organizations:

understanding written and unwritten agreements, Sage,

Rousseau, D. (2001), Schema, promise and mutuality: the building blocks of the psychological contract, Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 74, 511-541.

Schmitt, R. (2005), Systematic Metaphor Analysis as a Method of Qualitative Research, The Qualitative Report, 10(2): 358-394 Accessed 1st August, 2009: http://www.nova.edu/ssss/QR/QR10-2/schmitt.pdf.

Senge P. (1990), The Fifth Discipline, Doubleday

Senge, P., Kleiner, A., Roberts, C., Ross, R., Roth, G., Smith, B. (1999), The Dance of Change: the challenges of

sustaining momentum in learning organisations, Nicholas Brealey

Publishing,

Swan, J; Newell, S, Scarbrough, H., Hislop, D, (1999), Knowledge management and innovation: networks and networking. Journal of Knowledge Management, 3(4), 262-275.

Swan, J, Scarbrough, H., Robertson, M. (2002), The construction of “communities of practice” in the management of innovation, Management Learning, 33(4), 477-496.

Teece, D., Pisano, G., Shuen, A. (1997), Dynamic capabilities and strategic management, Strategic Management Journal, 18(7), 509-533.

Contact the Authors:

Associate Professor Deborah Blackman,

Dianne Phillips,