Strategic Management: A New Process For Decision-Making

And The Capitalization Of Knowledge

Jacques Lewkowicz, Centre de recherche

en gestion &

Myriam Lewkowicz, Laboratoire Technologie de la Coopération pour l'innovation et le Changement Organisationel

ABSTRACT:

After an analysis of the evolution of strategic thought, emphasizing the contribution of organizational learning theories based on resources, skills and organized training, we present a new conceptual system and model for knowledge capitalization. We present also the groupware Memo-Net and an example of its experimental use.

Introduction

The main object of this presentation is to propose a new system for decision-making, using the following three criteria:

(i) The overall strategy is viewed as a project in which the corresponding methods are applied

(ii) Strategy is examined from the perspective of the ongoing implementation, rather than for its content or ideation

(iii) However, the 'implementation' is considered to be the determining factor, in the process of formulation and determination of the content

Having established our work in the field of strategic thought evolution and revealed our own conceptual system, we will show how to use the DIPA method to solve problems of strategic management (according to the perspective stated above). We shall use an experimental example.

The Current Situation In The Evolution Of Strategic Thought

It is generally accepted that the concept of strategic thought begins with the LCAG model (Learned and al, 1965). In this model there is essentially an element of dichotomy: strengths/ weaknesses on one side, and opportunities/ threats on the other. The introduction of BCG type matrixes does not fundamentally change the conceptual approach. BCG reduces the strengths and weaknesses to one variable only : the market share; and the opportunities and threats to one single variable : the rate of growth of the market (BCG, 1980). The other matrixes (ADL, McKinsey) only complicated this rigid simplicity. Only the idea of the circulation of monetary liquidity between businesses of unequal maturity conforms to the longstanding practice of industrial holdings, and constitutes a real theoretical contribution. Ultimately, it concerns an exclusive approach by the market that will be taken up again by Porter (1980, 1985). From this paradigm, the competitive advantage comes through the ability of the enterprise to position itself well relative to its competitors; it provides itself with market power by introducing monopoly factors, such as the determination of supply. Its originality results in the concept of competition coming from factors other than the direct competitors, and above all in the concept of the 'value chain', meaning the investigation of those practices which specifically contribute to the competitive advantage.

The school of strategic thought based on resources and capabilities (Barney, 1990, 1995, 1996, Grant, 1991, Hamel and Prahalad, 1994) is very different since it places the competitive advantage on an idiosyncratic combination of both intangible and tangible assets[1]. But this specificity of acquired capabilities presupposes training; the main contributions of which are from Argyris and Schön (1978), who make the distinction between the simple loop (doing better than one has done before), and the double loop (doing everything differently than one has done before). Nonaka (1994) introduced the distinction between explicit knowledge and the tacit expertise; the distinction being more difficult to define as it is emerging (Reix, 1995).

It is this emergent characteristic that crosses the entire strategic process (Mintzberg and Waters, 1985). It also justifies the notion that one can regard the evolution of a business enterprise as being a punctuated equilibrium. The evolution would be characterized by an alternation between phases when the business maintains the same orientation as before, and other periods when crises call into question the previous trajectory or path (Tushman and Romanelli, 1985; Adizes, 1988). The evolutionist theory showed from its standpoint how the implementation of a technology can bring in irreversibilities, which will impede the development of businesses who use it (Dosi, 1982).

Punctuated equilibrium

assumes the corporation is driven by an autopoietic process (Von Krogh, Roos

and Slocum, 1994). Indeed, the cognitive current has shown that it is the

perception of the environment, self-produced by the members of the corporation,

that acts as a reference for them (Bougon, 1992). In this line of thought,

organizations are living entities capable of reproducing and developing by

their own means. One essential element of this process was identified in

organizational learning. This autopoietic approach can be outlined by contrast

to the rationalist approach, using table 1. In the autopoietic approach, the

organization is seen as a complex and

interconnected action circuit.

|

Nature of approach |

RATIONALIST AND PLANNING |

AUTOPOIETIC |

|

CHarac-tERISTICS |

In terms of the

relationship between action and uncertainty |

|

|

Lower uncertainty

and complexity of the decision to act by means of : - retrieval of

information; - analysis of

means related to goals. |

Action is, by

its nature, random : systematic research of causality fails to eliminate

chance |

|

|

In terms of the relationship

between conception (direction) and implementation |

||

|

Centralized

conception of implementation at the operational level |

It is essential

to identify emerging phenomena, which prompt the organization to

self-product. |

|

|

In terms of the

nature of information used to make the decision |

||

|

Normative and

scientist approach. |

Information is

never “merely observed” but built. |

|

Table 1 : Comparison between rationalizing and planning approaches and

autopoietic approaches.

Status Of Our Work

We place ourselves within this autopoietic current. We seek to determine those concepts that are conducive to strategic decision-making. The idea of project appears to us as a means to resolve this problem. It helps in investigating two fundamental components in the process of strategic planning:

¨ Strategic planning is the result of an exchange of argumentation among the actors

¨ Strategic planning is not conducted once and for all : it is a process of systematic renewal, independent of any predetermined agenda.

In this context, the exchange of argumentation is constantly renewed and thus nurtures a living process of organizational learning.

However, is this to say that we are abolishing any standard? As Levinthal and Warglien pointed out (1999): “planning the auto-organization” may seem a paradox. Indeed, a distinction must be made (from the most constraining to the least) between three levels of standards:

1. Standards in the content of strategic maneuvers (BCG or Porter types)

2. Standards in formulation and control procedures (strategic planning and goal-oriented management types)

3. Standards in concepts used for strategic organizational learning (such as that occurring in the management of a strategic project, where a solution develops gradually, instead of being a momentary choice between various alternatives, and where another factor is the pattern of relationships among participants whose roles are not interchangeable)

Our work falls into this third category and therefore does not rule out the prospect of auto-organization.

Moreover, recent papers on organizational change (Levinthal, 1998; Edwards, Braganza and Lambert, 2000) have held that the idea of opposition between incremental change and radical change must be abandoned. They add, however, that it is yet unclear how it should be abandoned, beyond punctuated equilibrium and Schumpeter’s creative destruction. Still, a persistent quest for a corporate consensus appears throughout these papers (Edwards, Braganza and Lambert, 2000).

In more operational terms, reengineering a process may seem an attractive prospect (Giard, 2000). What remains is to define, conceptually (in other words, beyond a mere call for caution) how to avoid the potential adverse reaction, likened by some to the blunders a surgeon can make, notwithstanding an excellent diagnosis, when operating blindfolded in a crowded room with a machete instead of a surgical knife (Strassmann, 1995; Robson, 1997). Orientation will eventually help to rediscover the importance of interaction between values, motivations, incentives, tasks, activities and organizational structures (Hendry, 1995). This standpoint can itself be attached to the idea of fostering individual employee involvement within an organization as a source of competitive edge (Pfeffer, 1999).

These elements must now converge towards the need to seek consensus which cannot be seen to be secured without the enhancement – not only technological but also architectural – of internal communication at least between the “senior managers” (Favier, Coat, Courbon and Trahand, 1998).

We propose a conceptual system of strategic and organizational change (regarded as two sides of a single effort) and a procedure (a model as well as a tool) to memorize the exchange of argumentation among the actors in the strategic planning project in order to formalize and reuse it when the need arises; the entire process will develop within a framework of organizational learning and memory.

This memorization will allow the organization to outline its “strategic trajectory,” in the sense defined by the TRASTRA conceptual system. But to enact it, the organization must develop a system of knowledge management. This is why we intend to investigate this sector first. These are the two fundamental elements in our approach, further examined below.

Fundamental Elements Of The Approach

Knowledge management

One attempt to classify styles of knowledge management (Zacklad and Grunstein, 1999) led to distinctions between three complementary approaches:

¨ Top-down: models are used (such as MKSM) to formalize the knowledge formulized by an expert

¨ Bottom-up: A corpus is used to build up a thesaurus (such as text or data-mining methods)

¨ Cooperative: the critical knowledge of organizations results, above all, from a collective competence that is poorly or badly formalized; the organization of interaction is scrutinized to come up with tools and methods for structured information, allowing better use of exchanged knowledge and facilitating reuse.

In light of our autopoietic stand, we will pursue this cooperative approach. Before elaborating it, we will present the TRASTRA conceptual system.

The conceptual system

We will examine the TRASTRA conceptual system and the DIPA problem solving method.

The

TRASTRA conceptual system

In this conceptual system (Lewkowicz, 1992), the development of companies can be regarded in terms of a Strategic Trajectory. To describe it, certain concepts need to be defined first.

¨ Strategy is a concept that features two elements, namely the strategy itself and the field of strategic forces:

- Strategy itself is defined as the search for consistency between the perception of external stimuli and the maintenance of control of the future by the company.

- The field of strategic forces is the structure of the set of forces that are likely to influence strategy (most importantly: customers, suppliers, human resources, real and/or potential competition, finance providers, institutional partners, groups with an impact on public opinion). These forces exhibit two characteristics:

§ their system of goals is only in part controlled by the enterprise;

§ their development in time depends in part on logic that is external to the enterprise.

¨ The “know-how” represents the existing and potential competence in the enterprise that is likely to propel it into a field of strategic forces.

¨ Regarding strategic maneuvers, with the due distinction between cost and differentiation maneuvers, the starting principle is to reject the idea that commitments are irreversible. The goal is to acknowledge the conditions for a potential reorientation in view of a different maneuver.

Thus, operations that are likely to contribute to the survival of an enterprise in a given field of competition forces are selected under the constraint of the “passed-down know-how” (available acquired skill) stemming from past decisions. These maneuvers contribute to the establishment of a “searched know-how.” A trajectory is therefore born out of the ongoing tension between these two dimensions of the know-how (see figure 1 below). The trajectory itself can be divided into “sequences,” each of them characterized by the alternative domination of the searched know-how or the passed-down know-how in the decisions that have a bearing on the choice of maneuver. The know-how, whether searched or passed-down, changes managers’ vision of the field of competition forces the enterprise is plunged into. It is therefore necessary to observe and describe the manner in which this constraint influences decision-making.

The appeal of this conceptualization resides in the idea that a conscious, articulated and explicit inventory, complete and achievable, of the strategic trajectory pursued by an enterprise, given adequate internal communication, enhances the creativity needed both in devising and implementing new strategic decisions. This statement relies on the following hypothesis: the enhancement resulting from an explicit strategic trajectory originates in the best mobilization of internal enterprise resources that can be afforded by this explicit character.

Indeed, producing a strategic trajectory is a way of summarizing past developments. Based on this synopsis, a new and more efficient process of knowledge creation can be built, oriented toward the future and aiming to “invent” a new strategy. The fundamental issue is not merely knowing who, why, under what circumstances and when has argued in favour of a particular strategic action. It is to grow awareness of the following phenomenon: each time the enterprise determines to implement a particular plan, it enforces on itself a number of constraints, which are necessarily cumulative. It thus forges a specific identity resulting from tangible and intangible assets: organizational routines (in the sense defined by Levitt and March, 1988), and resource and competence bases it must take into account for future strategic action. This identity can be viewed either as an opportunity given a supply of complementary actions, or as an obstacle to be removed in the future. A “truth” would thus come up from the past trajectory and from the range of future trajectories that are possible in view of the passed-down know-how. Within this hypothesis, each particular tactical decision is more easily merged into the global strategy of an enterprise once this “truth” is acknowledged. It also helps to mobilize internal resources as it strengthens the cultural and symbolic identity of the organization among its members. The goal, metaphorically speaking, is to transform the “know-how constraint” into a resource, through a better understanding of the origins of this constraint. This calls for a formalized process of strategic elaboration that nurtures a diversity of standpoints among the actors, leading to choices of strategic maneuvers that make up the sequence-based development. This is an area where research in Rational Design can be of help.

|

Passed-down know-how Searched know-how BEGINNING OF NEW STRATEGIC SEQUENCE Change of domination of one upon the

other TENSION between ELECTED STRATEGIC

MANEUVER Developments in the field of competitive forces Human resources management Organizational

structures |

Figure 1 : The jump from one strategic sequence to another

The DIPA

meta-model and knowledge capitalization

Most frequently in knowledge capitalization projects, it is not quantity but quality of information that is in short supply. This throws us back to the structure of memorized material. Consequently, the best way to locate and preserve the crucial knowledge being exchanged in these project networks (Grundstein, 1996) is to study the structure of interaction and come up with tools that systematize the structure of information, enhancing the value of exchanged information, and facilitating reuse.

Von Krogh, Roos and Slocum (1994) noted that organizational knowledge depends on “language implementation.” It is a limiting approach to conceptualize the organizational language as a static set of syntax, signs and codes that require consistent usage in time and space. In fact, the structural language of organizational knowledge is always able to create the reformulations it engenders, due to its capacity to phrase increasingly specific analyses. Nevertheless, as noted above, this ever-changing character of organizational knowledge must not impede efforts to formalize its constitution. Indeed, this formalization does not deny the autopoietic character of the constitution. It merely shows the possible shift from its implicit to its explicit nature (Nonaka, 1994).

For our part, we seek to provide certain suggestions as to the formalization of the constitution of organizational language. This constitution assumes a collection of information that can be broadcast by software tools issued from the field of CSCW (Computer-Supported Cooperative Work). Such software, also called groupware, brings with it a change of paradigm in information technology, since it deals with issues concerning the implementation of communication and coordination between humans, which is exactly the scope of the present paper, as opposed to researching human-machine interaction.

Still, while groupware can provide a record of the search for solutions (some of which are part of strategic management), to achieve effective knowledge management this alone is insufficient. Structured information must be added to the picture, and this can be attained by two different approaches:

¨ a posteriori : the structure of concepts produced is sought among traces of past interactions;

¨ a priori : interactions are enhanced “in real time“ so as to facilitate subsequent utilization.

We choose to investigate the latter approach in order to guarantee both an enhanced quality of interactions and an enhanced quality of recorded traces of interactions that allow for easier subsequent use. We also seek to avoid the proliferation of messages that tend to pollute exchanges (Favier, Coat, Courbon and Trahand, 1998)

Research in this segment of Rational Design (or “conception logic”) provides methods that allow for structured information and thus deal with issues arising in the process of emergence, articulation, representation and use of reasoning. This research aims to develop methods and computer-assisted representations that can be used to extract, maintain and reuse the reasons that led to conception decisions (i e. the goal is to memorize the chain of reasoning as realistically and inexpensively as possible, but also in a structured and clear manner) (McLean et al., 1989). Thus, that which was memorized can be understood and used by an outside person attempting to grasp the chartered object. Given that meetings consist centrally of unveiling and criticizing arguments, the purpose of Rational Design is to develop schematic representations that use computers to create, evaluate and modify arguments. The principal hypothesis is that when one devises arguments in this more explicit way, they can be more effectively utilized.

The methods most widely known and tried, such as IBIS (Issue-Based Information System) or QOC (Questions, Options, Criteria), have been criticized (Lewkowicz, Zacklad, 1998-a, 1998-b) for being poorly adapted to complex scenarios of collective conception, such as strategic management projects. We have therefore proposed a new model called DIPA (Diagnostic, Interpretation, Proposition, Approval) (Lewkowicz, Zacklad, 1999) that attempts to formalize the process of strategic decision-making based on organizational learning. DIPA has two branches – depending on whether the situation requires actors to focus on synthesis or analysis; in other words, whether the situation requires the shaping of solutions or a diagnosis.

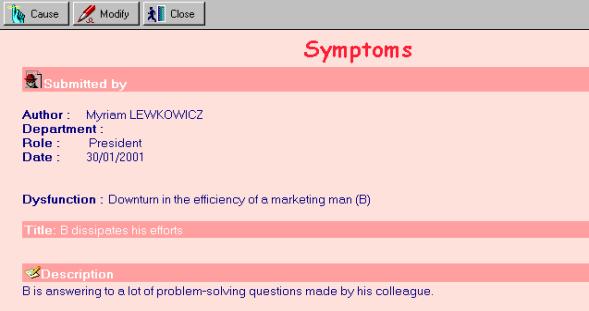

Within the DIPA model, reasoning unfolds in three major stages:

1. In the first stage, the problem is described and data are collected, viewed as symptoms in analysis situations- or as needs in synthesis situations

2. The second stage uses input data to find a matching interpretation that acts as possible cause in analysis situations or as a functional solution in synthesis situations

3. The third stage, implementation, uses the interpretation (cause or functionality) to devise a plan that serves as a reparation suppressing the causes of the symptom (analysis) or as a means consistent with the expressed functionality (synthesis)

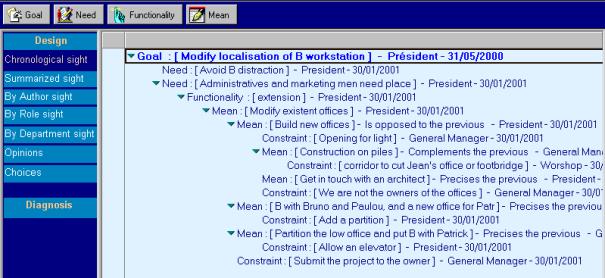

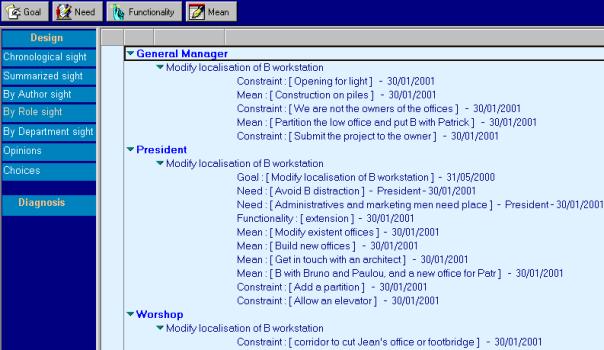

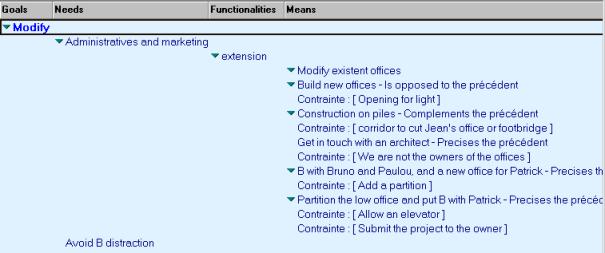

We have implemented the DIPA method to build a groupware product: MEMO-Net (Lewkowicz, Zacklad, 1999). This software tool comprises two modules, one for the synthesis stages (referred to as “conception” in the software interface), and one for analysis stages (“diagnostic” in the interface). It allows a project group to deal with issues that come up in the process of strategic planning by alternating the two activities in a cooperative fashion. Our vision is that strategic planning scenarios encompass two types of activities: one generating solutions in the form of strategic maneuvers, and another evaluating these solutions as a diagnosis of the strategic situation. Structured exchange allows users to control the decision making process and organize the principal arguments in a manner that improves their traceability and capitalization.

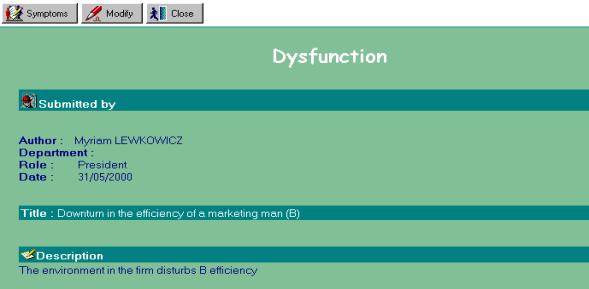

In the diagnostic module, the actors of the project group identify a malfunction and describe the symptoms, causes and reparations. In the conception module, once a goal is set forth, actors describe the needs, functionalities and means. In either situation, they can describe constraints or submit proposals to choose from. In this case, each user can input his opinion on the proposal and the person in charge can determine, in view of these opinions, whether the choice is final. Exchanges can be retrieved in chronological order or rated by concept name, author name, their role and services. Users contribute to the process by clicking on screen buttons and creating the appropriate records.

Figure 2: DIPA, a heuristic meta-model of reasoning and conception for analysis and synthesis

|

DIPA |

DIPA synthesis |

DIPA analysis |

|

Problem |

Goal |

Malfunction |

|

Input |

Need |

Symptom |

|

Interpretation |

Functionality |

Cause |

|

Abstract constraint |

Abstract constraint |

Abstract constraint |

|

Plan |

Means |

Reparation |

|

Concrete constraint |

Concrete constraint |

Concrete constraint |

|

Approval |

Choice |

Choice |

Table 2 : Implementation of the meta-model for synthesis (conception module in MEMO-Net) and analysis (diagnostic module in MEMO-Net)

An Experimental Example

For Mintzberg (1994), separating the production of strategy from its implementation is absurd. In fact, only the implementation of a strategy truly reveals its strength and weaknesses. The example we will present here is therefore deliberately related to the implementation of strategy within the autopoietic approach we have elected as our own.

The company where we have conducted our experiment is in the metallurgical industry. More specifically, it manufactures metal joints for the oil and nuclear industries. The company also has a mechanics and boiler section, and markets its products worldwide. The exchange of argumentation we helped to formalize aimed to improve the working conditions of one of the sales managers.

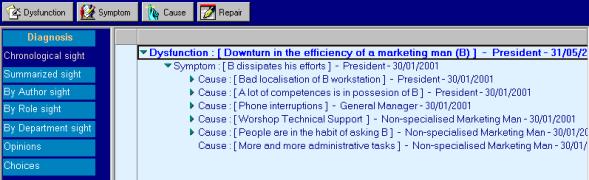

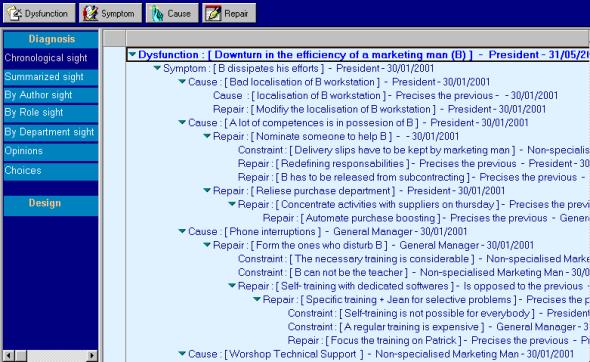

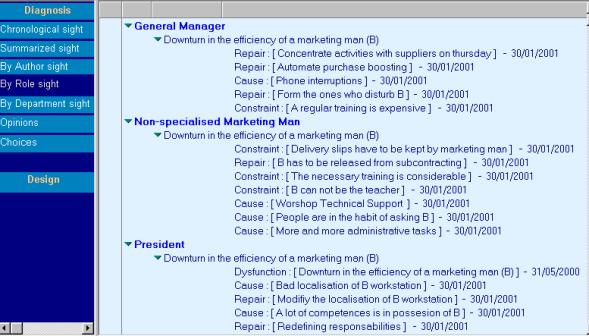

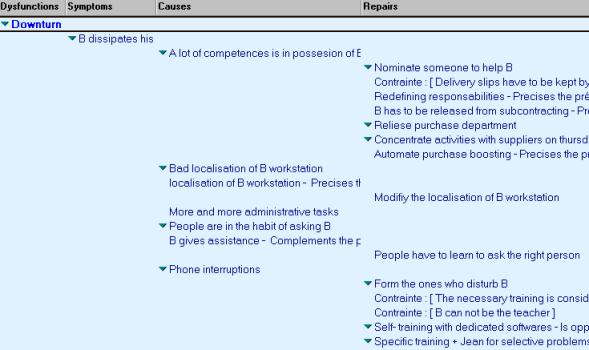

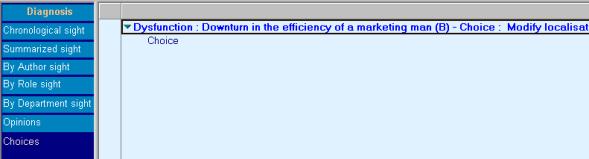

Below are screen shots of the MEMO-Net software used in this example. We have used both modules: conception and diagnostic:

¨ on one hand, the diagnostic of the problem has led to four decisions : three of organizational nature (delegation) and one concerning the physical displacement of a sales manager;

¨ on the other hand, we sought to identify the new location of the sales manager : by modifying the existing premises or building new ones.

In either case there is:

¨ a chronological view in condensed and exploded mode;

¨ a role view;

¨ a summary view;

¨ a choice view.

Samples of documents created in the process of exchanging argumentation are also available. The complete MEMO-Net database concerning this example can be found at the following address:

http://intranet.cog-net.fr/bases/memonet/memonet_spm.nsf

Diagnosis

Condensed chronological sight

Unfolded chronological sight

Sight by Roles

Sight summarized (by category)

Sight choice (or agreements)

Documents

Design

Unfolded chronological sight

Sight by roles

Sight summarized

NB. There is no sight choice

because no decision was fixed.

An analysis of the exchanged

argumentation revealed that the company hosting this experiment was undergoing

a period of transition between a passed-down metier based on essentially

technological competence and a demanded metier based on essentially

administrative and commercial competence. This exchange argumentation was

collected while being physically but not verbally present in a meeting where it

took place. This is the second stage of an experimental protocol designed to

demonstrate that acquired knowledge can be integrated fully and without

deformation into the tested communication device.

In fact, this exchange appeared as a process of making an emerging strategic decision because in the subsequent weeks the company determined to significantly broaden its plant space, a decision that not only comprised the one in question but also exceeded it. It really was a strategic decision because it involved the purchase of additional land, financed by a long-term loan.

Discussion

Regardless of the fact that the experiment must be extended to other fields for more validity, two other new steps are required to achieve our goal of building a tool for strategic decision preparation. The first attempts to verify the capability of DIPA and Memo-net to be used by the participants of strategic decision themselves in real time (during the time of argumentation exchange). The second attempts to measure what degree of satisfaction is determined by using DIPA and Memo-net in the production of a strategic decision

References

Adizes, I. (1988) Corporate Life Cycles: How And Why

Corporation Grow And Die And What To Do About It, Prentice -Hall, Inc.,

Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey.

Argyris C., Schön D. (1978) Organizational Learning, Addison-Wesley, Reading, Mass.

Barney, J. B. (1990) Firm

Ressources and Sustained Competitive Advantage, Journal of Management, 1, pp. 99-120.

Barney, J. B.

(1995) Looking Inside for Competitive Advantage, Academy of Management Executive, 4, pp. 49-61.

Barney, J. B.

(1996) The Resource-Based Theory of the Firm, Organization Science, 5, September-October, pp. 469.

Boston Consulting Group (1980) Les mécanismes fondamentaux de la compétitiivité,, Suresnes, Hommes et Techniques

Learned, E.P., Christensen, C.R., Andrews, K.R., Guth, W.D. (1965) Business Policy, Text and Cases, Richard D. Irwin, New York.

Bougon, M. P. (1992)

Congregate Cognitive Maps: A Unified Dynamic Theory Of Organization And Theory,

Journal of management studies, 29:3,

pp.369-389

Dosi, G.

(1982) Technological Paradigms and Technological Trajectories: A Suggested

Interpretation of the Determinants and Directions of Technical Change», Research Policy, 11, pp. 147-162

Favier, M., Coat, F., Courbon, J.-C., Trahand, J. (1998) Le travail en groupe à l’âge des réseaux, Economica

Grant, R. M.

(1991) The Resource-Based Theory of Competitive Advantage: Implications

for Strategy Formulation, California

Management Review, Spring, pp. 114-135.

Grundstein, M. (1996) La

capitalisation des connaissances de l’entreprise, une problématique de

management, in actes des 5ème Rencontres du Programme MCX,

Complexité : la stratégie de la reliance, Aix-en-Provence.

Hamel G., Prahalad, C. K.

(1994) Competing for the Future,

Harvard Business School Press, Boston.

Lewkowicz, J. (1992) Comment mieux intégrer la technologie dans la stratégie d'entreprise? Revue Française de gestion, no. 89

Lewkowicz M., Lewkowicz J. (1998) Design Rationale et prise de décision

stratégique dans l'entreprise, in Actes

du colloque Décisions sous contraintes, Presses de l’Université de Caen.

Lewkowicz, M., Zacklad, M. (1998-a) La capitalisation des connaissances tacites de conception à patir des traces des processus de prise de décision collective, Actes de la conférence Ingénierie des connaissances, Pont-à-Mousson.

Lewkowicz, M., Zacklad, M.

(1998-b) A Formalism For The Rationalization Of Decision-Making Processes In

Complex Collective Design Situations, in Proceedings of COOP, Cannes.

Lewkowicz, M., Zacklad, M. (1999) MEMO-net, un collecticiel utilisant la méthode de résolution de problème DIPA pour la capitalisation et la gestion des connaissances dans les projets de conception, IC99

Mac Lean, A., Young R.M.,

Moran .P. (1989) Design Rationale: The

Argument Beyond The Artefact, in Proceedings of CHI ’89, Austin Texas,

April 30-May 4 1989 ACM Press,

Mintzberg, H. (1994) The Rise And Fall Of Strategic Planning, Free Press, New York.

Mintzberg, H., Waters, J.A.

(1985) Of Strategies, Deliberate And Emergent, Strategic management journal, pp. 257-272.

Nonaka, I. (1994) A Dynamic

Theory Of Organizational Knowledge Creation, Organization science, 5:1, pp. 14-37.

Porter, M.E. (1980) Competitive Strategy: Techniques for

Analysing Industries and Competitors, Free Press, New York.

Porter, M.E. (1985) Competitive Advantage: Creating and

Sustaining Superior Performance, Free Press, New York.

Reix, R. (1995) Savoir tacite et savoir formalisé dans l’entreprise, Revue Française de Gestion, no 105, September-Ocotober, pp.17-28.

Tushman, M., Romanelli, E.

(1985) Organizational Evolution: A Metamorphosis Model Of Convergence And

Reorientation, in Cummings, L.L.,

Staw, B.M. (ed.) Research in organizational behavior, 7,

pp. 171-222, JAI Press, Greewich Ct.

Von Krogh, G., Roos, J.,

Slocum, K. (1994) An Essay On Corporate Epistemology, Strategic Management Journal, 15, pp. 53-71.

Zacklad, M., Grunstein, M. (Eds) (1999) Système d’information pour la capitalisation des connaissances: tendances récentes et approches industrielles, Hermès

Jacques Lewkowicz is post graduate from université de Paris I (Pantbéon-Sorbonne) and has a doctorate in business administration from Université d’Auvergne (Clermont- Ferrand). He can be reached at Faculté de Droit, d'Economie et de Gestion, Université de Pau et des Pays de l' Adour Avenue du Doyen Poplawski, BP 1633 64032 Pau-Cedex ; e-mail: Jacques.lewkowicz@univ-pau.fr .

Myriam Lewkowicz is postgraduate from Université de Paris IX (Dauphine) and has a doctorate in computer science from Université de Paris VI (Jussieu). She can be reached at Université de Technologie de Troyes 12 rue Marie Curie BP 2060 10010 Troyes Cedex ; e-mail: Myriam.lewkowicz@univ-troyes.fr